Posted on September 25, 2022 | 82 Comments

Here, I’m going to respond to Sean Domencic’s commentary on my article ‘Genesis and J. Baird Callicott’ published in my last post, and try to pick up on as many of the comments beneath it as I can (albeit too briefly or evasively, I regret). Sean’s commentary is an exemplary exercise in constructive criticism of a kind that’s all too rare, and also a lovely piece of writing in its own right. My thanks to him for taking the trouble to produce it.

I’ll engage with Sean’s commentary in a moment, but it’s been quite a while since I published the article it engages with (fourteen years, to be precise), so first I’m going to assess some of the positions I took there from the present perspective of my somewhat older self.

Looking back on it now, I have to concede that the view I took of human action in the world in my 2008 article was pretty bleak: “at the end of all our labours we shall still be hungry, and ignorant, and unredeemed”. I think it’s sage advice from Sean and other commenters to lighten up a bit. In my defence I’d say that I was trying to stress the need to be humble more than the need to be miserable, but I’d now row back a bit from the full-on tragedian take. Instead of ‘tragedy’, perhaps ‘difficult dilemmas’, ‘insuperable trade-offs’ or some such language might better serve. All the same, God’s curses in the Yahwist source do still sound pretty bleak to my ears: “Cursed is the ground because of you; in sorrow shall you eat of it all the days of your life. Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to you … in the sweat of your face shall you eat bread, till you return to the ground…for dust you are, and into dust shall you return”.

Talking of thorns and thistles, it’s probably relevant that I wrote my article just when I was beginning to establish my own small market garden, after a few years of reading and learning about organics, permaculture and other alternative or nature-friendly forms of farming. I think I was partly writing against an over-easy assumption commonly inflicted upon unsuspecting students by writers, teachers and other gurus in that world that if you just stick to their methods and embrace the balance of nature then your cup of plenty will overrun.

That’s rarely how it feels starting out as a fledgling commercial organic grower, battling market prices and obstructive bureaucracies as well as any number of crop pests and diseases. As I saw it then and largely still do, nature is less a balance than a stalemate, the sum total of a myriad organisms well fitted by a long evolutionary process to getting what they want from one other, albeit not without a struggle. I guess part of my thought process was that we in the alternative farming movement needed to get real and embrace the struggle like other organisms a little more.

But re-reading my piece again now, fresh from my recent critique of George Monbiot and his argument that farming is intrinsically destructive of the natural world, again I think I pressed my position a little too far in the tragic direction in a way that implicitly aligns with Monbiot. Both Monbiot and my 2008 self argue that agricultural interventions in the natural world inflict an unavoidably heavy cost, which leaves the door open to Monbiot’s view that it’s better to do away with farming altogether and replace it with something better, like the studge factories he favours.

Both my 2008 self and my 2022 one would unite around the view that studge factories are not better and will ultimately inflict an even heavier cost than most farm systems. The tragedy, or the trade-off, isn’t allayed so easily. Still, I don’t provide many resources in my 2008 article to resist whatever the latest dumbass idea might be for ‘saving’ humanity and nature from each other with some novel bit of high-tech whizz-bangery (one of Sean’s criticisms of it that I concede). I like Greg and Eric’s suggestions just to do the best you can in farming and not get too worked up about it. But for that to work systemically, I think there’s probably a need for a stronger underlying moral philosophy – and this is what Sean offers in his commentary.

Talking of high-tech whizz-bangery, space precludes me from discussing the role of science in our agrarian future which Clem raised in relation to Sean’s commentary (I do discuss it a bit in Chapter 16 of A Small Farm Future). In a nutshell, I’d suggest that the working scientists of today would do future generations a big favour if they strive to dissociate the name of science from its present entanglements with high-energy, high-capital, labour ‘saving’, export-oriented commodity farming favoured by governments and corporations (I recommend Glenn Davis Stone’s recent book The Agricultural Dilemma: How Not to Feed the World on this point).

A final point before I turn to Sean’s remarks. I remain critical of over-easy solutionism in the alternative agriculture or neo-agrarian movement as much as in high-energy modern agriculture. I’m probably as much if not more despairing now about what’s in store for humanity than I was in 2008, but in a more strictly agricultural sense I think I have lightened up a little. I still think we have to eat our bread in the sweat of our face, but alongside Greg I believe that ultimately people do find a way through the thorns and thistles towards a manageable, if always imperfect, agricultural practice. I’ll say more about that at the end of this post.

So now I’ll turn to Sean’s critique. I won’t try to summarize it – you can read it for yourself here. The key to it in my view is the wonderful and intricately argued section ‘Life as a gift’, which includes a lengthy quotation from John Paul II in which the theologian-pope propounds a different interpretation of the Eden story to my own.

Now, I can be a combative soul at times, but even I baulk at arguing scriptural interpretation with a pope. More to the point, I basically accept the logic of Sean’s (and John Paul’s) argument in this whole section. It’s clearly the case that God didn’t just fire Adam and Eve from the team, contract not renewed, condemning them and (metaphorically) us their descendants to a wholly alienated and disenchanted eternity. As Sean rightly implies, there’s an implicit commitment to at least the theoretical goodness or redeemability of humanity in my account, and I erred in failing to incorporate this explicitly. I find much of Sean’s more detailed argument about the Christian interpretation of this point fascinating and convincing. Here’s my attempt to gloss it briefly in secular terms: there is something true and good in the world beyond any specific instantiation of it in human practice, but from a human perspective it can be mobilized only in human practice.

This is basically a non-modern or anti-modern position with big implications for the nature of political society – another interesting arena of debate that I’ve had with Sean and others and that I plan to address in the future (and, with apologies, Evan, I must reserve discussion of your points about citizenship until that occasion. Likewise thanks to Don for your kind remarks and your excellent idea of a ‘Romantic Anti-Capitalism’ reader, which perhaps we can pick up again when we get further into the politics).

Anyway, all this is to say that I basically accept the logic of Sean’s exposition of the gift, and his correction or extension of the arguments in my article.

Things get slightly trickier when we turn to practical implications. To get into that, here are a couple of quotations from Sean’s piece:

Man is simultaneously limited by the Divine Order of natural law and given dominion over Creation, which he must ‘till and keep’ for the glory of God. In short, man is the ‘jewel of creation’

It is possible for human dominion to simultaneously remain humble and to avoid arrogating God’s sovereignty to itself, because humanity is contained in the divine hierarchy.

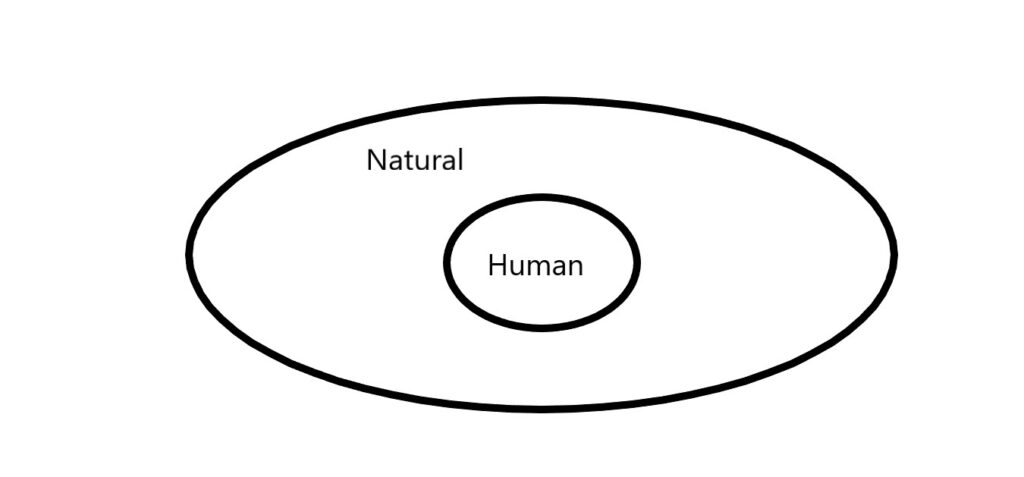

Before proceeding, I probably need to say something about the concept of ‘hierarchy’. I think Sean is referring to a more technical meaning of the word than its everyday modern use to mean a ladder-like ranking of who’s up and who’s down, like a football league table. Instead, hierarchy really means a differentiated structure of parts and encompassing wholes. It can be illustrated with this diagram, which relates to present concerns.

There is a biosphere on Earth we call ‘nature’. It contains human beings, and many other kinds of organism. This is an encompassing whole. But at the level of the human, we differentiate ourselves from nature. We are human, a part of nature, but also differentiated from it – things that may apply at the level of the natural don’t necessarily apply at the level of the human. Nor is this hierarchy necessarily ranked – neither humans nor nature are necessarily the better part. But if the hierarchy is ranked, the ordering can be reversed at different levels of encompassment. From a human perspective, for example, the life of an individual human always counts for more than the life of an individual fly, whereas at the more encompassing level of the whole of nature this isn’t necessarily the case.

The same diagram can serve for a different hierarchy – Sean’s ‘divine hierarchy’ – if we relabel the encompassing whole as the divine or the godhead instead of nature. But in this case there’s a one-way ranking. The human is inferior to the divine, respectively the receiver and the giver of the gift.

Perhaps we can also bring the two diagrams together. The divine encompasses nature, which encompasses humanity. The divine stands above both, whereas humanity as the ‘jewel of creation’ normally stands above nature, but also sometimes (ultimately?) stands beneath and serves it.

A couple of points here, the first of them something of a side issue that perhaps can be discussed another day. I’d suggest that my tragic interpretation of the Eden story remains basically valid but it is, as it were, a ‘lower’ truth that’s contained within the human part of the hierarchy, and it’s reversed by the higher truth that Sean invokes of divine love. To be honest, I find it hard not to read the Eden story as an account of the sundering of humanity from nature and the origin of the nature/human hierarchy – the origin, too, of a certain tragedy, or at least of certain ‘insuperable trade-offs’, in humanity’s self-conscious alienation from nature. But that doesn’t negate the encompassment or redemption at a higher level that Sean discusses. Possibly, it does raise questions about how to construe the rational, interior, personal human consciousness and its origins that he also discusses, but lest I end up arguing with the pope after all, I think I’ll leave that thought there. I’m not sure the origin of consciousness is a vital point of difference in this discussion.

The bigger issue for me is Sean’s critique of my hesitancy, not only in my 2008 article but also in my more recent book, about articulating what he calls “specific doctrines about how the world works, how it ought to be, and how to change it”.

Since debating with him post-publication of my book, I’ve been on something of a path of convergence or part-convergence with Sean’s natural law approach. I agree with him on the need for a first principles rather than an empirical approach to defining the parameters of the good life in ways that engage and motivate people, and I accept that my writings to date have barely done this. Indeed, I’ve been taken to task by less sympathetic critics than Sean on the same point along the lines of “OK, OK, so a small farm future – but how?”.

I suspect Sean and I agree that the answer to that ‘how’ isn’t some modernist piece of quick fix solutionism – market incentives, class struggle, nationalist assertion or some such. I’m coming to think instead that the ‘specific doctrines’ undergirding a small farm future will only emerge long-term through deep cultural change, even if the collapsing certainties of the modern world order might hurry it along a bit. In this, they might resemble the slow emergence of the natural law tradition Sean invokes, just as a more unified later medieval political culture in Europe reconfigured itself out of its classical and Christian precursors in the collapsed shell of the Roman empire.

As I’ve already said, I plan to engage with the politics of this long transition another time. What Sean gives us in his commentary is an overarching intellectual framework for it. To my mind this is a considerable gift, but it hasn’t entirely satisfied some of the other commenters on this site. They’ve argued that in view of the disintegrative forces at large in the world today, time isn’t on our side in building a new political culture equal to the challenges of our times – and if we can’t build it soon enough, those disintegrative forces may prevent us from building it at all. Joe Clarkson pushes this line further, arguing “I suggest that we just let everyone do what they want based on their best judgement/prejudice/stupidity and let evolution sort it out. That’s what happens anyway; why fight it?”

I’d argue that that’s pretty much what modern political and moral philosophy has done, and evolution is beginning to have its say on the matter. If we’re to escape the harsh judgments it’s likely to hand down (possibly harsher yet than God’s judgments upon Adam and Eve) then I think we do need to fight it. And to fight it, we’ll need better ways of constructing our societies than we’ve managed of late. To me, Sean’s approach seems helpful in this respect.

In a response to such objections under an earlier post of mine, Sean wrote:

I agree with Chris that citizens will have [to] construct their social order, but I propose an addendum: that they ought to construct it based as closely upon reality as they can manage. If they do a half-decent job at constructing a public square which is genuinely ‘commensurable’ between citizens (unlike that of modern ideology) by being true to the reality in which we all share, then they will return to the natural law tradition, one way or another.

I think that’s a good response, although I do have some misgivings about it. I’m also aware that some people will find this whole discussion pretty abstract and pointlessly intellectual in the light of present pressing realities. To me, it’s not pointless because – as I’ve just said – we need better ways of constructing our societies than we’ve managed of late, and discussions like this are one part of that building work.

Still, it’s true that these discussions are quite intellectual and abstract. So I do wonder if Sean’s criticism that my writings don’t give enough of a bold political vision or something for people to get excited about in their hearts might also apply to his own analysis?

Anyway, in A Small Farm Future I tentatively moved beyond what Sean nicely calls the ‘bucket of ice cold Somerset existentialism’ on offer in my 2008 article towards an engagement with civic republicanism, virtue ethics and perhaps the natural law traditions that he upholds. All this was something of a gap in my education that I’ve only lately started to fill – my debates with Sean have unquestionably helped with the filling, and thanks to his input I think I’ll be able to offer an improved grasp of the politics of small farm societies in the future.

I also largely agree with another of Sean’s comments that

There’s a modern(ist) temptation to try to propose an ideology which will “end history” and solve all the problems of fallible, sinful/selfish human beings forever. I don’t claim that natural law politics is offering that….There will always be many different interpretations, especially when applied to more and more particular situations, but fortunately a lot of the difficult theoretical thinking has already been done, and we can continue to draw on that traditional wisdom.

But here I would add that we’re now facing some unprecedented ‘particular situations’, and if we manage to restore the importance of that traditional wisdom or even remember it as we face them, a lot of difficult work still remains to be done to breathe life into them anew. What will certainly fail is any attempt to impose natural law politics top down as a quick fix solution to the ills of the present. In this respect, the pushback from various traditional Catholics and secular conservatives against the idea that Sean and I among others have had of creating a broad-based Distributist Congress to engage in this work that includes non-Catholics and non-conservatives hasn’t filled me with confidence. Is the traditional wisdom Sean upholds strong and supple enough to overcome the ideological schisms of the present and build bridges across contemporary religious and political divides?

The ills of the present that I mentioned stem in considerable part from human hubris in our modern sense of ourselves as conquerors of nature. In my 2008 article, I therefore invoked the Eden story as a tale of human nemesis salutary for present times, but I do believe Sean is right to suggest I overdid it in supposing it to be little more than that. Still, I worry that he pushes too far the other way with his account of humanity as ‘the jewel of creation’ and his conviction that it’s possible for human dominion to simultaneously remain humble and avoid arrogating God’s sovereignty to itself. I accept his point that the Christian tradition offers some defences against hubris, but I’m not sure they’re strong enough – which is partly why we’re in our present predicaments, and also why attempts to build a new distributism already seem mired in schism. Inasmuch as those defences involve recourse to higher truths than earthly human affairs, I worry that the gatekeepers of these higher truths in tradition-ordered societies can too easily corrupt themselves and their subordinates with all too human power games.

These misgivings parallel ones raised by Eric and Andrew. Yet while they’re important, I think they’re less significant than the genuine improvements to my vision that Sean’s commentary effects. Here, I agree with Andrew that a moral-religious vision of the kind Sean provides is more likely to succeed in placing the necessary limits around human behaviour than a tragic one, especially if it’s satisfactorily embodied in politics – politics being the missing term here that I suspect we’d all agree needs more fleshing out (something, once again, that I intend to do as soon as I can). I’d only add that tragedy probably can’t be banished altogether, because any adequately complex morality probably involves worldly contradiction, and contradiction breeds tragedy. Or at least dilemmas.

Meanwhile, I wonder if it’s also worth thinking about the embodiment of human morality in ecology, which in fact was a key motivation for Callicott’s original piece.

In my 2008 article I mentioned the idea that humans fit the ecological niche of ‘patch disturbers’, alongside others of our kind such as elephants and beavers. But I didn’t make much of the point, and I think I erred in what I did make of it by talking (albeit with an element of irony) about ‘the patch-disturbing evil within our hearts’. As I now see it, ecologically and morally, through the lens of Aldo Leopold’s land ethics or Sean’s Christian virtue ethics, I’d say that patch disturbance can be good or it can be bad, depending on circumstances (one of the problems with George Monbiot’s ecological vision is that he seems to see no circumstances in which human patch disturbance can ever be good). Contemporary fossil-fuelled global capitalism represents ecological patch disturbance on an epic scale, and it is not good.

But some years down the line in my career from my 2008 article, I’m a bit more relaxed about certain kinds of human patch disturbance than I was back then. So I wonder if there’s scope for a kind of secular-ecological version of the Christian morality of redemption that Sean sketches when he writes: “It is true to say that we are “frustrated gods” if we can only grasp at divinity; but we are joyfully divinized if we receive the Gift of God: the most perfect of gifts, in which He gives Himself to humanity, in the Person of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Perhaps, if only as an imperfect analogy, we might say that likewise we are frustrated ecomodern gods if we grasp at interacting with zero impact on the biotic community of organisms conceived in some state of perfect balance, but if we can joyfully empty ourselves into a role as knowing patch-disturbers seeking the gift of sustenance from the world like (but also unlike) other organisms, life becomes more hopeful.

Maybe, then, patch disturbance or keystone species behaviour is a higher-level ecological practice than the stalemate of nature, just as – following the logic of hierarchy I outlined above – virtue ethics is a higher-level ethical practice than living tragically in nature.

I fear we’re a pretty long way from any such higher-level ecological practice as a species right now, but I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of achieving it in the long term. With a few more years under my belt as a disturber of the earth than in 2008, I’ve learned quite a bit more about making a livelihood from it. This includes knowing more about how little I know about things I didn’t even know I didn’t know back then. So whereas in 2008 I was a bit paralyzed by the tragedy of not knowing what I was doing, I now draw more comfort from the fact that, painfully and incrementally, nowadays I don’t know what I’m doing at slightly more expansive and sophisticated levels of ignorance.

The Yahwist narrative is, as Joel implies in his comment, deeply concerned with agriculture and agricultural relations. If that’s not already obvious in the story of Adam and Eve, it becomes crystal clear in the story of their sons, Cain and Abel. Joel asks how this plays in the context of aboriginal cultures, such as the Australians subjugated by the European descendants of Cain.

Others can answer that better than me, and I’ve already run on too long, but what I’ll say in brief is that I think there’s a global need now to develop local societies as if they’re aboriginal ones even though we know they’re not – and the Yahwist narrative together with Sean’s natural law framework can help in the task. I don’t think the possibly implied distinction between agricultural and foraging societies is important any more. But I do think the greater emphasis on equality in certain aboriginal cosmological hierarchies of individual-community-divinity than in the Christian divine hierarchy might be.

Anyway, to finish on a practical note I believe we need to develop right agricultures that are patch disturbing at the appropriate scale. And since we’ve recently been talking about wheat harvesting here, I’ll leave you with a photo of the most scale-appropriate technology for cutting and threshing the main ingredient of the staff of life that we’ve yet hit upon here at Vallis Veg, courtesy in part from a gift freely given by a valued member of the Small Farm Future community. In the sweat of our face…

In this respect, the pushback from various traditional Catholics and secular conservatives against the idea that Sean and I among others have had of creating a broad-based Distributist Congress to engage in this work that includes non-Catholics and non-conservatives hasn’t filled me with confidence.

Is this something you’re at liberty to expand upon?

It’s all on Twitter: not a place (nor a debate) worth spending too much time on!

the pushback from various traditional Catholics and secular conservatives against the idea that Sean and I among others have had of creating a broad-based Distributist Congress to engage in this work that includes non-Catholics and non-conservatives hasn’t filled me with confidence

Nor me; though it has also helped me to find some more like-minded people with similar interests. So there’s that.

Thanks Chris for continuing to hack at the weeds that have overgrown this path.

I fully sympathize with the “…small farm future – but how?” question, but even if a large number of us knew the exact answer and worked our hardest to enact it, there is still no guarantee of success.

Accordingly, I have a strong attraction for Joe’s “…let evolution sort it out…” approach.

Although I’m not averse to a little communitarian effort. Still, my hopes are very low.

My first guess at an effective approach may sound awfully new-agey, but what has worked for me is to set my intentions to a particular goal, and as I make daily decisions, continue toward that goal. In the present tense, it seems like nothing is happening, but looking back at a few years, it’s shocking how much change can happen in tiny increments.

Yes, “…ideological schisms of the present…”. Precisely what many of your arguments with various ‘experts’ here have been about, eh?

My guess is that those ideological schisms will become very much less meaningful (in the near future) when our next meal will hinge on how we treated our local soil this afternoon.

And “…patch disturbance can be good or it can be bad…”.

Amen to that.

Though it seems to me that much of the difference comes down to the scale of the disturbance.

I applaud both Chris and Sean for their placement of first principles first.

But maybe I should also say that I regard the establishment of ‘first principles’ or religion to be a component of Joe’s evolutionary process too.

I’d vote for one of the first principles to be an attempt at tolerance of others’ first principles. There are few ecological disasters more destructive than war.

Thanks Eric! A counter-proposal to consider: Jesus of Nazareth was very /intolerant/ of a lot other’s first principles (especially the pagan Romans), but He had a very unique way of proclaiming the Truth of His own first principles: peacefully, lovingly, suffering and dying for them.

If your first principles include that I should not exist, we have a problem.

Thanks Chris for this great reply with so much to discuss! I have a dreadfully busy weak ahead, but I hope to prioritize a reply to this soon. So many topics you raise to make for great discussion.

Thanks for the comments. Look forward to your reply Sean, when you get the chance. So I’ll pick up further discussion after that.

Indeed there’s a case for not taking the death-by-soundbite world of Twitter too seriously. On the other hand, I’d consider some of the protagonists to be real players with views that are representative of ones that are out here in the world, so it’s an issue… Anyway, I hope to discuss this more in due course.

Further biblical support for the idea of stewardship, I think, can be found in Psalm 104 (https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%20104&version=NIV) which amplifies the Genesis creation story and a Gift if ever there was one. That dominion over the Earth did not equate to licence is also suggested in Job Chapter 38, which also extols the virtues of Creation, but commences with the following admonishment:-

Then the Lord spoke to Job out of the storm. He said:

2 “Who is this that obscures my plans

with words without knowledge?

3 Brace yourself like a man;

I will question you,

and you shall answer me.

4 “Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation?

Tell me, if you understand.

5 Who marked off its dimensions? Surely you know!

Who stretched a measuring line across it?

6 On what were its footings set,

or who laid its cornerstone—

7 while the morning stars sang together

and all the angels[a] shouted for joy?…

Thanks for this Chris, a very interesting meditation on all sorts of elements within this conversation. I like the way you’ve put your own writing into the context of your life at the time.

I’m interested in what you find valuable in Sean’s interpretation. Several times you state that it’s a better way, or a higher order way, to understand the Genesis story, or that it provides a useful intellectual framework. However, it seems to me that you don’t really accept most of it. The exception is the idea of the gift, which you reframe as the ‘gift of sustenance’ provided by the world.

Your disagreement seems to me to centre on hierarchy. Sean’s vision is, I think, articulated around a patriarchal order, in which humanity are children (or servants?) in God’s house. You map that onto the notion of humanity as dependent on Nature, but I don’t think that gets us very far because the implications of Sean’s interpretation are essentially moral (that humanity should follow God’s laws), whereas I don’t think you see humanity’s dependence on Nature as necessarily conferring any particular moral injunctions.

Of course, the whole point of this discussion is focused on morality. Given that humans have a choice about how they treat the world, how then should they treat it, and how can particular choices be justified? If we are to follow the moral tenets that emerge from Sean’s story, we have to commit to his version of Christian belief. Your story is secular and your main point concerns the basic structuring of human awareness and imaginative capacity set within the wider world – there is no real moral component to that story, instead it emphasises trade-offs and dilemmas. Humans can still act any way they like, it’s just that they’ll likely come to different kinds of grief depending on which way they turn.

But I think you do come closer to a moral element towards the end when you state the importance of equality to your outlook. Equality is a moral injunction because it affects choices – require that humans should do certain things even where they can do others. It doesn’t emerge from either yours or Sean’s analysis of the Genesis story though – indeed, I don’t think it would sit well with the implications of Sean’s natural law approach.

But I do think that it has very interesting implications when applied to your points about patch disturbance. One of the most objectionable elements of Monbiot’s ecomodernist vision is the autocratic human society that would need to be created in order to keep humanity locked away from pristine Nature and dependent on industrial studge. An acceptance of patch disturbance that also insists on equality in human society prompts the creation of very different kinds of community.

Sometimes your writing puts me in mind of the kind of discussions that characterised seventeenth-century debates on liberty and the kinds of society that promoted it. This is no doubt in part because of your interest in civic republicanism, which also informed some of those discussions. But I wonder if it might also offer you a way of promoting the kind of society that we all agree is needed. Liberty is still a resonant concept, and one in which moral injunctions can find a grounding.

Joe Clarkson pushes this line further, arguing “I suggest that we just let everyone do what they want based on their best judgement/prejudice/stupidity and let evolution sort it out. That’s what happens anyway; why fight it?”

I’d argue that that’s pretty much what modern political and moral philosophy has done, and evolution is beginning to have its say on the matter. If we’re to escape the harsh judgments it’s likely to hand down (possibly harsher yet than God’s judgments upon Adam and Eve) then I think we do need to fight it.

What is ‘it’ we need to be fighting? If ‘it’ is evolution, then my follow-up would be “Good luck”. But in one sense or another from our distant ancestors to our gene editing neighbors we have been bent on fighting evolution for a very long time. Some might argue with a little bit of success. But there is still the issue of what exactly does success look like.

If ‘it’ is the human behavior under past and present political and moral philosophy – then is the fight we need to wage one to find a better path? Then if once we coalesce around such a different path our efforts will again be subject to some adjudication; evolution, or the judgement(s) of a deity. Once such a judgement comes down, will we all agree on it? Will we accept it?

What is IT ?

It is financialation of everything , everything must have a price in dollars and cents , the most beautiful paintings are valued not as paintings but as what someone will pay for it . even your body has a price with my health insurance it’s three million dollars !

They know the price of everything and the value of nothing .

Thanks for the new comments – appreciated. I’ll await Sean’s response before responding to them much further myself, but for now a few remarks for clarification just in respect of Clem & Kathryn’s comments.

Clem, the ‘it’ I was referring to indeed was evolution, and the sense I meant it conforms very much to your point that we’ve been fighting it for a long time with some success, but also with some doubt about what ‘success’ means. At its barest, the fight is to stay alive and to reproduce (in this sense, I’m not convinced there’s a parallel in culture). More generally, I see it as a matter of call and response – nobody and nothing can entirely control the response, but given that humans (pre or post Eden…) have some self-consciousness about it we do have the capacity to condition the response by controlling our call. So if, for example, I say we shouldn’t burn through remaining fossil fuel reserves and render humanity almost certainly extinct by raising average global temperatures by 8 degrees, I don’t think a good response would be to say ‘well, you can’t fight evolution’.

That, however, has been pretty much exactly the response of various modernist ideologies such as eugenics and laissez faire economics, which have adopted an empirical rather than ‘first principles’ ethical position in respect of issues such as famines and illnesses – per Diogenes’s point. So to Kathryn’s point I’d suggest that while a first principles approach to ethics does not in itself guarantee it will endorse anyone’s right to exist (and therefore might very well be problematic), it’s more likely to do so than empirical ones, as per doctrines such as Jeremy Bentham’s or Carl Schmitt’s.

However, I do agree that there are some difficulties concerning agreement over first principles ethics and who gets to gatekeep them, which is where the political complement to this post comes in. And I will write about this…soon. Provided the British government’s current experiments in empirical ethics allow it.

I mean, I don’t think the current British government is experimenting with empirical ethics, I think they’re experimenting with looting. But thank you: yes, while a “first principles first” approach doesn’t exclude the possibility of horror, but a purely empirical approach almost guarantees that “might equals right” will rear its ugly head

I think one thing that muddies the waters here is when people attempt to impose what they see as virtues (or even second-order principles) on others. Clearly, people who think homosexual relationships (for example) are inherently sinful should refrain from having them; but I’m much less convinced by efforts to prevent others from having those relationships, or from having them recognised on their own terms, or by efforts to claim that such relationships are a new and evil development, or whatever.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t attempt to identify or develop first principles and work from them; but rather that a certain amount of humility in the interpretation and application of those principles to the real lives of real people is important. It would be heretical of me to add anything to the Apostle’s Creed, but I am frequently concerned (and sadly not surprised) by the behaviour of some of my siblings in Christ, and I sometimes wish the relevant churchmen had included something more specific about how we are to treat one another in their formulation rather than leaving us to work out the implications for ourselves. (Apparently Jesus telling people, sometimes at great length, to love their neighbour as themselves is insufficient for this to have taken root in some cases.)

That’s all very bleak, or perhaps tragic is the better word. But my question is really the same as my twitter question about eugenics etc: how do we include as many people as possible, without exposing one another to actual danger?

…guess I’d argue that looting is an example of empirical ethics, along the lines of “I do because I can”. I have an element of sympathy when poor people loot, on the “well they started it” principle. Not, of course, a justification that applies to the British government.

I agree, though, that it’s easy to slip from defining first principle virtue into mere social ranking, that humility in relation to people’s behaviour is an important defence against it, that Jesus’s teachings contribute to that defence, and that alas those teachings and parallel ones have often not been taken to heart by Christians and non-Christians alike.

I’ll try to address your question about danger when I write about virtue politics. I find it difficult territory. On the one hand, it strikes me that there can be a bit of slippage among liberals/leftists from a right to question someone’s values to a ‘right to exist’. On the other hand, I’m sympathetic to slippery slope arguments – and when we’re in a country where letting people drown at sea has almost attained mainstream acceptability I fear we’re a long way down it.

“when we’re in a country where letting people drown at sea”

Who is holding a gun at their heads making them get in a boat ?

Many people are drowning in the Rio Grande crossing from Mexico ( 200+) this year so far , two million have crossed the border this year counted by border patrol plus perhaps as many as another million have slipped across unseen , Eagle Pass has run out of space in the graveyard the bodies , they are found out on ranches , one rancher finding a body a month this year .

Open borders are giving us another genocide conveniently ignored by the media ,many Texas border towns are bankrupt some are even firing teachers , roads go unprepared hospitals close , crime exploded , many ranchers now carry a loaded pistol after they and their vehicles have been shot at .

Some of the border crossers are going back , they have found that the USA is just another failed state , billionaires run the country the rest are just the same peasants as their own country , paid more but just as poor .

Who is holding a gun at their heads making them get in a boat ?

Depends. In Central America it might be a drug cartel. In the Middle East (Syria) it might be Bashar al-Assad.

Cuba

Haiti

Venezuela

Columbia

Honduras

…

not too many folks headed toward those borders.

There are difficulties here in the US. But on the whole they tend to look small compared to other spots on the planet.

You couldn’t pay me to move to the USA, so people who go there must be pretty desperate. 200 deaths in 2 million crossings seems like pretty good odds, especially if you’re certain you’ll die if you stay where you are.

Too bad about the lack of gun control, too; it’s hard to fathom that level of violence, here.

If it’s such a failed state, have you thought about leaving? Why/why not?

I have a huge amount of sympathy for poor people who engage in behaviour labelled by the right-wing press as “looting”. In many cases I wonder whether “opportunistic reparations” might be a more accurate framing.

I don’t mind having my values questioned, in good faith. I don’t mind having my actions challenged, especially if I am doing harm, though I won’t claim to always enjoy the process. These are not usually threats to my existence or expressions of a desire for me to not exist; they can be, at best, real indications of esteem, insofar as they indicate that people believe I can do better.

But I’m not going to stop being disabled or queer or foreign or female, and there is plenty of evidence that some people really would rather I don’t exist, or else exist only to serve their needs, on the basis of those traits. There is plenty of evidence that this would be a thousand times worse if my disabilities were more obvious or severe, or if I had brown skin, or if I happened to have a wife rather than a husband.

I don’t really know how to counter these ideas. For me it comes back to humanism, and Christian humanism at that: the idea that every person born has immutable worth and value is, for me, inextricable from my religious beliefs about the nature of humanity. I don’t mind if others have a different route to the same conclusions, and I’m always happy to discuss what that humanism means for how we actually live our lives.

I don’t think you can single-handedly make the dangers of fascism go away. I do think being clear that fascism is a danger, and that it is unwelcome, is an important part of not attracting fascists to a discussion. I think it is especially important in a discussion in which imposition of “traditional” or “conservative” values (scare quotes because their own claims about such traditions are often a bit dodgy) is seen as desirable by a large (or perhaps merely loud?) contingent.

The drug cartels are already here , that’s why Texas big city murder rates are getting out of control , the Governor has declared the cartels terrorist groups , many border crossers pay between 10and 20% of their earnings to the cartels , this is for life , they are cartel slaves , if they go back to where they come from they are murdered , that’s the gun at their head .

I like the phrasing of “empirical ethics” versus “virtue ethics”!

On second thought, perhaps I’d rather juxtapose “evolutionary ethics” versus “virtue ethics”, since both are genuinely empirical: one according to reductionist mechanism and the other other according to classical philosophy.

(Aside: please forgive poor grammar, I shouldn’t attempt to write comments on my phone really)

Chris,

Thanks again for this great response: I’ve basically written another post! I’ll start with justifying our conversations, some points of agreement, and then move on to address three concerns of yours that you raise.

TRUTH, AND OTHER INVISIBLE REALITIES

I think the fruitfulness of this conversation is grounded on a mutual pursuit of Truth. You write that you agree with “the need for a first principles rather than an empirical approach to defining the parameters of the good life in ways that engage and motivate people, and I accept that my writings to date have barely done this.” I’ve seen some people in the comments question the “abstractness” of these conversations. I won’t deny that our topic here is abstract, but I take issue with the idea that this makes it either useless for “real life” or impossible for finding common ground. A wise man once said that “life is more than food and the body more than clothes” (Luke 12:23): conversations about visible realities (like producing food and fuel) are more useful to our “animal” desires for food, shelter, etc, and they are more easy to come to agreement on. But conversations about invisible realities (like love, friendship, familial bonds, virtue, duty, culture, religion) are utterly essential to our distinctly human desires for happiness and fulfillment, even if they are very difficult to find agreement on. I propose the difficulty to find agreement is not based on the /un/reality of these things (is anyone here going to say that love isn’t real?), but because our knowledge of invisible realities requires both empirical-but-non-numerical observation and virtuous living–neither of which are popular in our modern ideologies of mechanistic individualism.

To those who dismiss all forms of common knowledge (“scientia”) about invisible realities, all of this may seem like silly language games. But for those open to the idea, I think the very proposal is “a bold political vision.” Recall that on the modernist notion of reality, “love”, “family”, and “beauty” are either entirely subjective and/or entirely reducible to physical phenomena of atoms and void. The classical philosophic tradition has a broader view of Reality, which seeks the Truth of these wonderful things which give our life meaning, and I think that rather than ivory tower quibbling, this is “something for people to get excited about in their hearts.” As Chris glosses it in “secular terms”: “there is something true and good in the world beyond any specific instantiation of it in human practice” (though, of course, we can only ever observe it through human practice).

THE MEANING OF HIERARCHY

I’m glad that you brought up hierarchy in the philosophic sense. In modernity, we tend to always imagine hierarchy as the imposition of an external, stronger power which extracts something from a weaker victim. You try to get away from that by proposing “hierarchy really means a differentiated structure of parts and encompassing wholes.” That’s a better definition: as an example, in the human body, the brain is “greater” than the foot, because it is more integral to the life of the body. But there’s also a deeper meaning to hierarchy in classical philosophy when we consider those ‘invisible realities’ I like to talk so much about. In this view, something is “lesser” when it is a relative analogy of the thing that is “greater.” Said another way, the “lesser” /participates/ in the “greater” by finding its fulfillment in the “greater. For example, the art of rudder-making is determined by the art of ship-making. The greater thing (ship-making) is prior and superior to the lesser thing, not in a way that externally dominates it, but in a way that communicates reality down from expansive things to specific things. Without ships, there are no rudders. Through this line of reasoning, many philosophers (of diverse religious backgrounds) arrive at the conclusion that there is a Source (a.k.a. Pure Being, Being Itself, God) which is “greater” than all limited beings which /participate/ to varying degrees and in diverse ways in Infinite Being. Everything that /exists/ is subordinate to the Source of Existence, not because the power of the Almighty is being violently or externally forced on us, but because what I call “me” would not exist without my Creator.

With all of this said, this makes it true amoung created things that “if the hierarchy is ranked, the ordering can be reversed at different levels of encompassment.” Is a chair or a bed “better”? Well, are you sitting or sleeping? Is the baker or an engineer “better”? Well, do you want bread or a house?

But it’s also true that some things participate in Being in a uniquely encompassing manner, as “cornerstones” or “lynchpins” of Truth and Goodness being communicated down through the hierarchy. This is where the idea of the “Chain of Being” comes in. But I’ll drop that point for a moment before returning to our discussion of man’s place in the cosmos.

REASON AND FAITH

You seek to harmonize our reads on Eden saying, “I’d suggest that my tragic interpretation of the Eden story remains basically valid but it is, as it were, a ‘lower’ truth that’s contained within the human part of the hierarchy, and it’s reversed by the higher truth that Sean invokes of divine love.” I more or less agree.

In Catholic philosophy, we have a distinction between things that can be known by natural Reason (philosophy) and things known by supernatural Faith (theology). In this case, I can agree that Reason can conclude that the world is “fallen,” i.e. subject to unavoidable pain, suffering, and futility; but that I know by Faith in Jesus Christ that the world remains suffused with the spirit of its original gift. These truths–as all truths of philosophy or theology–come from different sources, but are harmonious. This same distinction is behind my general appeal to the “natural” virtues (justice, prudence, temperance, courage) and the classical philosophic tradition: the Catholic Church has observed, confirmed, and synthesized these ideas with the Gospel (which adds the “theological” virtues: faith, hope, and love), but She doesn’t claim that only Catholics can know or practice the things which many philosophers learn by reason. (I’ll also note, per MacIntyre, that reason isn’t purely individual, but an inherently social and traditional faculty!)

However, as Andrew has pointed out, while you generously acknowledge the Catholic claims about the Gift are “higher truths,” you don’t necessarily accept their source. Reason can tell us a good deal about the /nature/ of the Divine, humanity, and Creation… but it can’t answer certain foundational narrative questions about how these things fit together within (eschatological) history: /why/ are we here? What comes /next/? /How/ do we fit into the cosmic narrative? Answering those questions is precisely what unifies the Judeo-Christian Scriptures. But if those are not accepted as God-breathed, then what other source for this narrative do we turn to? This, too, I’ll return to in a moment, as I move to your concerns.

CONCERN I: Objective Truth may be Politically Intolerant

There are some people (*cough* New Natural Law goons *cough*) who use the language of natural law, seeking to “update” it to modern conditions, but are really just doing conservative liberalism. I appreciate that you grasp that wide gulf between natural law theory and liberalism, the former being “a non-modern or anti-modern position with big implications for the nature of political society.” (Some have proposed we take a “meta-modern” position…)

Now I want to be entirely clear that I have ZERO interest in the modern nation-state taking up performative traditionalism and making, as you say, “any attempt to impose natural law politics top down as a quick fix solution to the ills of the present.” That’s exactly what Fascism was, and what certain elements of the Reactionary-Right are trying to do now. As my colleague Michael Hanby has written critiquing this doomed project: “technological revolution governs us more deeply than the rule of law ever could.” There can be no serious nor successful return to the natural law tradition without a return to ecological economics.

Still, I think that return can and must happen more quickly than you suggest. You suggest a “slow emergence” like that of the middle ages out of the “collapsed shell” of Rome. But as you also point out: time is not on our side. I think we need more of a renaissance than a re-emergence. It seems (to me) that your concern is that there are so many ugly (and they are beastly!) reactionary and right-wing associations with natural law and classical philosophy that they could not be reliably used to further a liberatory project.

I propose that just as “the working scientists of today would do future generations a big favour if they strive to dissociate the name of science from its present entanglements [liberal capitalist technocracy],” that’s precisely what needs to be done with virtue ethics &c from its present entanglements [reactionary politics], and we Distributists are the ones to do it.

You ask “is the traditional wisdom Sean upholds strong and supple enough to overcome the ideological schisms of the present and build bridges across contemporary religious and political divides?” Before answering that, I think we need to ask a more important question: is this traditional wisdom /true/? If so, it is our only worthwhile choice, and it will surely provide whatever we need. I notice that a large number of eco-leftists types will praise “traditional wisdom” and “ancient philosophy” in various forms… but remain unwilling to commit to any of them. I think that position leaves us in the halls of postmodern academia: endlessly deconstructing ourselves, but never building an alternative. Every building requires a foundation, and we remain facing the choice for our own: classical philosophy (which considers invisible realities and the authority of Truth and Goodness) and modern ideology (which reduces all things to private gain and mechanistic power). Perhaps it’s a point worth debating, but I see all the “third options” between the two as incoherent mixtures, often made by modernists who want the veneer of antiquity without the obligations.

CONCERN II: Existing Religious/Philosophical Institutions are too Inflexible

A related concern is that the gatekeepers of all things Old will prevent them from being used to the service of all things New.

First, I’ll note that philosophy has no gatekeepers: anyone can read Aristotle, Plato, Aquinas, or MacIntyre. If someone believes in their rational arguments for Truth or Goodness, she isn’t automatically signed up in the Registry of Platonists and billed for dues–though she may find herself morally and intellectually compelled to start living differently. And the very fact that I can include MacIntyre (still living!)–who began his work as a Marxist and found virtue ethics necessary to critique capitalism–on the list shows the supple flexibility of classical philosophy to provide guidance and answers to our modern questions and crises.

But the Catholic Church, I have to admit, has gatekeepers: Bishops, Popes, Councils, Doctrines, Creeds. Indeed the image of keeping the gate is quite literal: “And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven” (Matthew 16:19). We see this as a gift from God, to keep wayward humanity from going astray (as we so often do) and to preserve the teachings of Jesus Christ both unsullied from distortion and eternally relevant to the present day. On this point of being relevant, you note that “there’s a global need now to develop local societies as if they’re aboriginal ones even though we know they’re not.” I agree, and can point to some excellent resources which point out the ecological through-line which exists not only in Genesis, but in the entire Biblical narrative. My inspiration into all these conversations is also strongly guided by Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’ which calls for “ecological conversion and spirituality,” a turning away from “throwaway, consumerist culture” and rooting ourselves in what we hope may become a “cultural ecology” (which he links to indigeneity). (Laudato Si’, to be clear, is not just a private musing, but an “encyclical”, which is a binding teaching document of the Church.)

Nonetheless, many eco-leftists look to the historic sins of the Church, of which there are many, and want to break off into some altogether new religious identity. For the primitivists, Kacynski, for example, proposes that we need an ideology/religion of “Nature” (in the footnote of ISAIF 184, he dismisses Catholicism as “stagnant”). New Agers and Neo-Pagans (Wicca being a popular form, among many stitched together “nature-based” religions) propose some kind of vague, broadly egalitarian worship of the natural world. But I think these strains of thought are all essentially sophistry: religion makes claim about the Divine (the foundation of reality, in a metaphysical sense) and our relation to the Divine (which includes publicly recognizing this Reality through social-rituals). If the Coven of Druids wants to burn sage to Odin as a hobby, it’s very unimposing, but if they want to engage with politics, they must either do so on the terms of the prevailing ideologies or through some kind of truly neo-pagan politics, which will then proceed to build the sort of social structures which (if successful) will eventually commit the sins of tyranny. The fact that liberalism, socialism, and nationalism have become religions in the name of “secularism” is proof that there is no society without gatekeepers of higher truths, whether a tribal lineage of Storykeepers, a Levitical Priesthood, or a gnostic cabal of murderous human sacrificers (Economists).

So it is true that “the gatekeepers of these higher truths in tradition-ordered societies can too easily corrupt themselves.” But, I’ll note, that Christianity does something unique on this front. While, as above, the Church claims very universal gate-keeping on faith and morals (even to the point of infallibility), She also preaches that every Christian is baptized into the prophetic vocation of Jesus Christ. The Spirit goes where He wills, not merely through the Church’s ministers, and so He is everywhere calling the Church (both leaders and members alike) to repentance, renewal, and development. This is, for example, why you find St. Catherine of Sienna (a mystic woman) chastising the Avignon Popes. Or the Second Vatican Council whipping away many reactionary attachments forged in the 19th century. As David Bentley Hart puts it in a (characteristically) poetically insightful thought not entirely agreeable essay: “Even in its most redoubtable and enduring historical forms, Christianity is filled with an indomitable and subversive ferment, an inner force of dissolution that refuses to crystallize into something inert or stable, but that instead insists upon dispersing itself into the future ever again, to destroy what confines it and to start anew, to begin again in the formless realm of spirit rather than of flesh, of spirit rather than of the letter. There is, simply said, a distinct element of the ungovernable and seditious within the Gospel’s power to persuade, one that we ignore only at the cost of fundamentally misunderstanding its most essential character.” For the Christian, the Kingdom of God (as I’ve pointed out before, an utterly unique concept) is always “at hand.”

And this brings us to:

CONCERN III: Humanism doesn’t seem to line up with Ecological Ethics

I think we agree that distributist farming (and other land-ethic civilizational practices) has the most limited and balanced ecological cost: “patch disturbance or keystone species behaviour is a higher-level ecological practice than the stalemate of nature.” But you “worry that [I] push too far the other way with [my] account of humanity as ‘the jewel of creation’ and [my] conviction that it’s possible for human dominion to simultaneously remain humble and avoid arrogating God’s sovereignty to itself.” So you say later on that we may need “the greater emphasis on equality in certain aboriginal cosmological hierarchies of individual-community-divinity” than the more patriarchial hierarchies of Christianity.

Two simple counterpoints: first, I question how much an egalitarian cosmos /generally/ exists in aboriginal metaphysics. The Great Spirit is a common figure across cultures. In animist worship of natural things (the sun, the sea, the mountain, etc), certain landmarks tend to dominate as supreme. And because animals, stars, and landmarks are /not/ actually the Divine, there have to be some “priests” (shamans, etc) who mediate and maintain the superstitions and customs associated with these idols. As such systems of “localized” gods become large-scale, this becomes an easy way for the tyrannical temple complexes to develop, as DOE admits as a backdrop to whatever egalitarianisms did exist in antediluvian days.

Second, the Christian emphasis on the dignity of the human person is the only reason we have values like universal human rights. The fact that we want distributism for the sake of liberty, equality, and fraternity of the whole human race is because we locate in human life the most important thing in the cosmos: humans are the reason that justice, beauty, and love can be articulated and enjoyed. In classical philosophy, man’s dignity is found in that he is a bridge between the material and immaterial: he is a fusion of body and soul. Humans are the ones who communicate rationality, by our ability to know Truth and morally act for the Good, down from the Divine into the material world. I don’t see any way that something /other/ than humanity can be acknowledged in this role… without ultimately leading to the subjection and sacrifice of human beings to an irrational object elevated as an idol.

I hesitate to engage again, but I’ll give it a go since my name and prior comment have been repeatedly mentioned.

My “why fight it” comment was made in the context of a discussion about man’s relationship to the land and, I thought, how best to organize that relationship in the context of a small farm future. Within that context, there appeared to be a very cordial dispute about the best way to approach the organizing process, a dispute which resulted in two different approaches, which I’ll too-briefly summarize as follows:

Chris’s position – “I argued that the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden dramatized human hubris in supposing ourselves to have godlike powers of judgment, and the consequent nemesis of our Fall and subsequent career as self-conscious, failed, would-be gods who can never get their interventions in the natural world quite right”.

Sean’s position – Our “only choice is to return to classical philosophy inquiry about what is true, good, beautiful, natural, just, etc—and to treat these questions with the same seriousness that the worshipers of Growth, Progress, and Money treat their predictions and prophecies about the Market”.

I sympathize completely with Chris’s approach, in which we can never have complete, godlike knowledge about what might work and what won’t. That approach also means we must therefore remain humble about specifying the political structure(s) of a small farm future. Chris seems bothered by the inherent uncertainty and attracted to Sean’s confident certainty, but I suggest that the ultimate in humility is not to even attempt the specification process (something that has been struggled with here at long length) and just let things work themselves out. Some things will work, and carry on, and others won’t and will die out. Let our small farm future evolve.

I don’t like Sean’s approach and my comment about evolution was an attempt at a somewhat wry reference to what happens when religious dogma about what is “true, good, beautiful, natural, just” is taken as a final authority. “Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius.” is a phrase reportedly spoken by the commander of the Albigensian Crusade, prior to the massacre at Béziers on 22 July 1209. Loosely translated as, “Kill them all; let God sort them out”, it shows the power of religious certainty when making decisions about the moral characteristics or behaviors of other people. As an atheist, I shy away from that kind of certainty. Sean apparently does not.

Letting evolution “sort it out” is what must be done when we don’t have the certainty of religion and must look around, see how the world really works and let that reality affect our judgement. When we do, we find evolution at the core of biology (indeed, just about everything).

Letting evolution sort it out also has the advantage of centering our approach to politics on an existential foundation. Not only does “existence precede essence”, in Sartre’s sense that we create the essence of what we are as individuals after we come into existence, but it also cautions us about how little sense it makes to spend time and energy talking about the essence of things that don’t exist. In the realm of biological creatures, where humans are irrevocably placed, existence (evolutionary survival as a species) is the summum bonum. You can talk about Divine Truth all you want, but the survivors write the bibles.

My comment also suggested that the same evolutionary reasoning could be applied to human cultures. Cultures evolve and cultural fitness is evidenced by evolutionary success. Success is again defined by survival. I think if we want to fight that process by specifying cultural optimization from first principles, we are doomed to failure. We may get lucky and specify the structure of a culture that actually survives, but the odds are against it.

Nonetheless, it is certainly possible to make aesthetic judgements about different cultural characteristics, including religion, science, technology and many others. I certainly have my aesthetic biases and we could talk at length about what is culturally lovely or ugly (modernity is ugly), but that’s for another day (or never).

Joe, I don’t adopt Sean’s position, but I must admit that I don’t find yours any better. Despite claiming a humble position with respect to the world, you seem very certain of the ultimate power of evolution.

Evolution is a concept – a representation of how we humans understand change to occur in the world among certain kinds of organism, which we have created and developed through collective endeavour and discussion over time. As a concept used for discussion and thought, evolution is an invisible thing, but not thereby a non-existent thing, as I’m sure you’d agree.

But you seem to want to make it the supreme governing principle in the world – and by that, I mean that you seem to want us to use it as a way of shutting down other ways that we might engage with the world. Instead, you propose what look to be supreme maxims: that success be defined by survival, and that survival should be one criterion by which we judge the fitness of cultures. When looking out across the world at the many ideas that people have about changing their cultures and building new ones to better flourish in the world, you seem to say: “Ignore them all. Let evolution sort them out.”

And yet I don’t believe you yourself live by the maxims of evolution. When you ‘look around’ and ‘see how the world really works’, you don’t rely solely on your own experiences. You use all sorts of shared concepts to think about it, to discuss it with others, to learn from them and to pass on your own knowledge. You engage in a wider human world, bigger than the specific ecological niche you carve out for yourself, so it’s very much a choice to say that it’s pointless to contribute to broader conceptual discussions about different approaches to living in the world, and will judge everyone else solely on the post-facto criterion of whether they survive. By appealing to evolution to justify that choice, you’re trying to make it look natural, just part of how the world works, but the mere fact that you contribute so many interesting comments to Chris’s blog, seeking to pass on knowledge, to learn, and to change minds, shows that it’s not how the human world works at all.

Nobody knows the future, but that doesn’t stop any of us from trying to shape it. In any case, cultures aren’t really organisms that live and die, they’re fields through which we engage and collaborate with one another. Change is their only real law, and all of us who live through them will die in the end. In my view what truly matters is whether we flourish during our time here, and discussing how best to do that seems very worthwhile.

Andrew,

To your point that I “engage in a wider human world, bigger than the specific ecological niche (I) carve out for (my)self, so it’s very much a choice to say that it’s pointless to contribute to broader conceptual discussions about different approaches to living in the world” – I never said that different approaches to living in the world were pointless (nor discussions about them), only that how well those approaches will work out in the future is difficult to know and will be measured by whether they persist, not by whether they are underpinned by religious doctrine.

I will also say that the system dynamics of biological and cultural evolution are so complicated that it is difficult to predict which approaches will be fit and which will be unfit. We can all marshal evidence for what will succeed and what will fail; I do it all the time when I rail against the damage modernity is doing to the living world. But, to me, a couple of things are clear: predictions about future success for any given approach are very difficult and should be based on evidence (I’ll say it, scientific evidence) and that success for living creatures, including us humans, means not going extinct.

We should remain humble about the limits to human knowledge, though. Even wiith mountains of scientific evidence, I doubt that it is possible to design a successful culture from scratch. The interplay of cultural variability and environmental selection is well worth studying, but it is so complicated that it is difficult to understand what happened after the fact, much less predict what’s going to happen in the future. It would be like asking a biologist to design and build a completely new creature that could thrive in the jungles of Borneo for a million years, something that would be impossible, even if he could build any creature he wanted, but something that natural selection does endlessly.

The same difficulty applies to designing the perfect culture for a small farm future. It’s hard enough finding a few leverage points that might nudge humanity in the direction of a small farm future, (leverage points we haven’t found yet, by the way) it’s impossible to figure out what kind of politics those farmers should have that will work out for the next X number of years. I would love to see someone develop the powers of Hari Seldon’s psychohistory (from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy), but I know it’s just fiction.

I do think there is solid evidence that a culture of small farming has more adaptive fitness than an industrial civilization built on a one-time slug of fossil fuels, but there is little evidence in the historical record that tells us which political structure we should pick for a small farm culture. Human history is filled with lots of different small farm cultures and political systems, cultures and systems that lasted many millennia. Evolution did the picking in the past and will do it in the future. Isn’t that enough?

Joe

Do you think Sean is trying to make claims about what will work for survival, or about what principles we might follow to make that survival worthwhile? It seems to me that he is trying to articulate a vision of a community which is not only surviving, but also good and just and virtuous.

Yes, Kathryn, that is exactly what Sean is doing, and that’s the problem. Whose goodness, whose justice and whose virtue?

Joe

Perhaps one key to this is in how we manage differences of belief about what is good, what is just etc, and the constant temptation to compel others to abide by our standards.

How can we find values in common without discussion? I think that we can’t. And if “let evolution sort it out” is not going to mean “the social group most willing and able to shoot people is the last one standing” then I think we *do* need to at least agree on not killing one another when we find ourselves in competition for resources.

Conversely, how can anyone make truly virtuous choices (by whatever definition of virtue) if compelled? A referendum at gunpoint is not democracy; a charitable donation made under threat of lethal force is not compassion. Imposing virtue on another is somewhat nonsensical.

So another way to frame the whole thing, I think, might be to ask how we can work toward conditions in which all people have, at least, the option of virtue, the option of participation in some kind of mutual flourishing. I don’t think that can include force, whether that force comes from a religious authority or the barrel of a gun.

I agree, but it may not be possible for humans to live without eventually using force against each other. While the capability for violence might be part of our nature, we have managed to survive on this earth for a long time despite that being the case. Violence against “enemies” has long been an integral part of most cultures without worldwide ill effect. It has never been maladaptive until recent centuries. Please note my reply to Andrew, below.

Thanks for the response, Joe.

I do think it may be possible for humans to coexist without doing terrible violence to one another; perhaps that makes me a naive optimist. But even if I am wrong and peace (without compulsion!) is impossible, I think it is worth trying to get as close as we can.

Further, I don’t think I necessarily agree that pre-modernity, violence was not “maladaptive”. Evolution is about fitness to survive and reproduce in a given environment; that environment changes (even without human intervention, though currently our actions are the biggest drivers of environmental change), and every individual who has ever been murdered before reproducing could have been someone with the unique genetic material to enable us to survive… something. Lack of diversity is inherently maladaptive in a changing environment, and lethal violence by its very nature reduces diversity.

But even if that weren’t the case I wouldn’t be okay with murder, partly because a society in which people are free to murder one another without reprimand is not one I want to live in, and not one in which I would last very long.

And even if *that* weren’t the case, I might well argue that murder is wrong because of the effect on the murderer. We could get into the cultural or social effects there, but I think it would be pretty difficult for me to separate it from my religious beliefs. But even on a practical level, if your go-to way of solving problems is to kill people, you’d better hope you don’t kill the only person in the area who knows how to set a bone, or make a sharp blade, or whatever. Once someone is dead they can never help you again.

This probably isn’t the time or place to get into discussions on when killing another human in the course of self-defence is warranted, “just war” theory, and so on. These are hard enough problems even when everyone in the conversation agrees that killing is generally wrong.

I’d second all Kathryn’s points here. Joe, since our earlier discussion the ‘evolutionary’ terminology you’re using to describe human societies has really jumped out at me – ‘maladaptive’, ‘fitness’ – and at the risk of sounding like a stuck record I think it’s really important to stress the capacity of humans to change their behaviour, and so counter ‘environmental’ dangers that they might otherwise succumb to.

A big part of the reason that people find it so hard to change now is the effect of large-scale power structures that make it hard to organise sufficiently to make a difference – it’s not simply because of our ‘nature’, we’re not just naturally averse to changing anything even when it seems most necessary. Graeber and Wengrow’s book was in part about the human capacity to experiment with social organisation and asked specifically we seem to have gotten stuck at our current juncture.

If there are some who resort to violence when things get difficult (and of course there are) then being prepared to defend ourselves is important, but it’s no solution, any more than women-only train carriages are a solution to misogynistic violence. We have to try to build peaceful societies.

Joe,

I can abhor and condemn the murders of the Albigensian Crusades as a betrayal of the Gospel and of the natural law. But how can your evolutionary ethics do so? On that view, it’s just the Catholic culture engaged in “survival of the fittest” against the Cathar culture, and there’s no room for moral outrage at the cruel certainty of anyone.

Are you, as an atheist, /certain/ that invisible truths have no place in politics, and that we can only evaluate the world according to the interaction of physical/biological/sociological forces? If so, I think there may be some atrocities that /your/ certainty needs to answer for… (Cavanaugh’s “Myth of Religious Violence” is an important study here)

It’s just the Catholic culture engaged in “survival of the fittest” against the Cathar culture, and there’s no room for moral outrage at the cruel certainty of anyone.

That’s pretty much it, except that while there’s plenty of room for moral outrage everywhere, there’s no “invisible truth” that provides certain justification for that outrage.

Just about every human behavior and atrocity that are possible to be outraged about have been accepted as normal, even exemplary, by some culture or another. This is why it can be so easy to slaughter each other.

And while I certainly have the average ability to be outraged (don’t get me started on Donald Trump), I know that my outrage is a product of my upbringing and social conditioning, not something that is justified or underpinned by an eternal truth writ large across the heavens.

I found cultural relativism a hard pill to swallow after being brought up in, and indoctrinated by, my culture. At first it was depressing to find out that my opinion of what was great and good were specific to my culture and that people from other cultures might have different views. It certainly took the edge off any ambitions for “success”.

It got a little easier to accept after living in a couple of different cultures for a few years each, but I still have the prejudices and habits of thought typical of a modern white American. I don’t try to fight it too much, since I live in the US, but I don’t let it overwhelm me with anger at “strange and deviant” activities in other cultures either.

Cultural relativism is a religious doctrine of the materialist ideology of Liberalism, by which many of our ruling class are indoctrinated. It should not be forgotten how friendly the New Atheists have been with the last few decades of “anti-terrorist” warmongers and neoliberal techno-optimists. Why do you allow this superstitious belief to overwhelm you with disdain for the many “strange and deviant” cultures and religions who belief in objective Truth and Goodness? Indeed, why even bother arguing against Theists and Virtue Ethicists, when you acknowledge the unknowability and amorality of everyone’s philosophic claims?

Fascinating back-and-forth as ever brings the zen-inflected last verse of the pretty song Truth Serum to mind:

People people there’s a lesson here plain to see,

There’s no truth in you

There’s no truth in me

The truth is between

The truth is between

I’ll link to the more rousing recent track though – songs often partake in my processing of life in dark times and light – with the wry last lines ‘Two million years of data, humans still in mode Beta, despite natural information.’ Natural information … that’s kind of what runs through the mind whenever I draw a fresh bucket of water up from the well. It’s cloudy now (lots of rain).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SlfltG9Wdc&list=RD4SlfltG9Wdc&start_radio=1

So many words. So little useful information.