Posted on October 17, 2022 | 56 Comments

I’ve now blogged my way through Parts I-III of A Small Farm Future in this marathon cycle of posts. Only Part IV remains. But before I get onto that (…this is why it’s been such a marathon), I want to devote a few posts to various other issues – some of them reiterations or clarifications of things in the book I’ve already discussed here, some of them touching on older concerns of this blog or issues that I lacked the space to address in the book, and some of them engaging with the growing list of people who publicly disagree with me about something or other.

I’m going to start with one of those ‘issues I lacked the space to address in the book’, namely health and social welfare in a small farm future. Actually, I did write a chapter about this but then cut it from the final version because I needed to reduce the word count and I felt the chapter wasn’t especially illuminating. Partly, this was because it was caught on the horns of a writing dilemma I’ve previously discussed, in trying to steer between bold blueprints and honest handwringing about the difficulties involved.

Anyway, several people have suggested it would be a good idea for me to address this issue. They’re probably right, so here goes. I’m going to make a few general remarks about it in this post, some slightly more specific ones in the following post, and then in the one after that I’ll publish the ‘missing’ chapter.

At the risk of starting on an overly defensive note, my first question concerning how to characterize welfare provision in a small farm future is, compared to what? It sometimes seems that lurking behind questions about welfare in a small farm future is an implicit sense that it’ll be so much worse than today that arguments for a small farm future lack prima facie credibility.

In response, I’d argue firstly that health and welfare provision isn’t that great as things stand right now for a great many, perhaps the majority, of the world’s people, and secondly that on present trends it’s more likely to get worse than better, even if we retain highly capitalized, energized and urbanized societies long into the future. More importantly I’d also argue that when you throw in the reality of melting ice caps, melting capital reserves, melting energy capacities and melting climatic, oceanic and geopolitical stability in the coming years, the capacity of any imaginable future society to take good care of people’s health and welfare is in doubt.

Still, it remains reasonable to ask what welfare provision might look like in future societies geared around agrarian localism, where the livelihoods of many are based on providing their own food and fibre. Reasonable to ask, but hard to answer in detail – so much depends on the unknowable facts of the transition and their consequences. But I’ll try to hazard a few guesses.

To assist in the guesswork, it will help to grasp some basic realities of present welfare provision. For simplicity and familiarity, I’ll stick with my home country of the UK. I imagine the basic points I’m making apply more widely, especially to other wealthy countries.

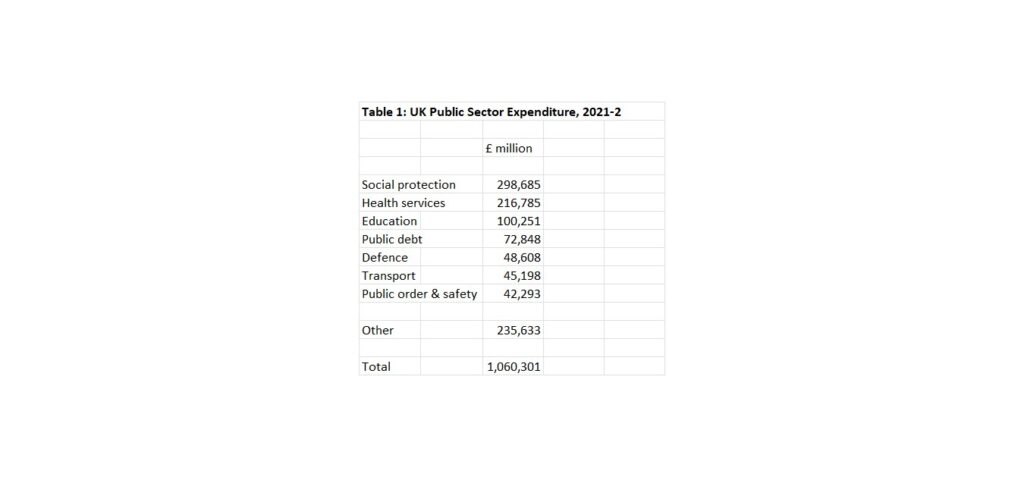

Table 1 gives a breakdown of where the approximately £1 trillion of UK government expenditure in 2021-22 went. It shows just the largest seven items, which between them swallowed almost 80% of the spending (the source for the data is here).

Much the largest single item at 28% of total spend is social protection, encompassing welfare benefits and social services. The largest single item of expenditure within this 28% is old age pension payments, comprising nearly 40% of it, with sickness and disability payments second (21%).

The next largest item is health services, comprising 20% of total government expenditure, with education a distant third at 10%. The remaining four items summed together account for a little bit less than the total spent on health.

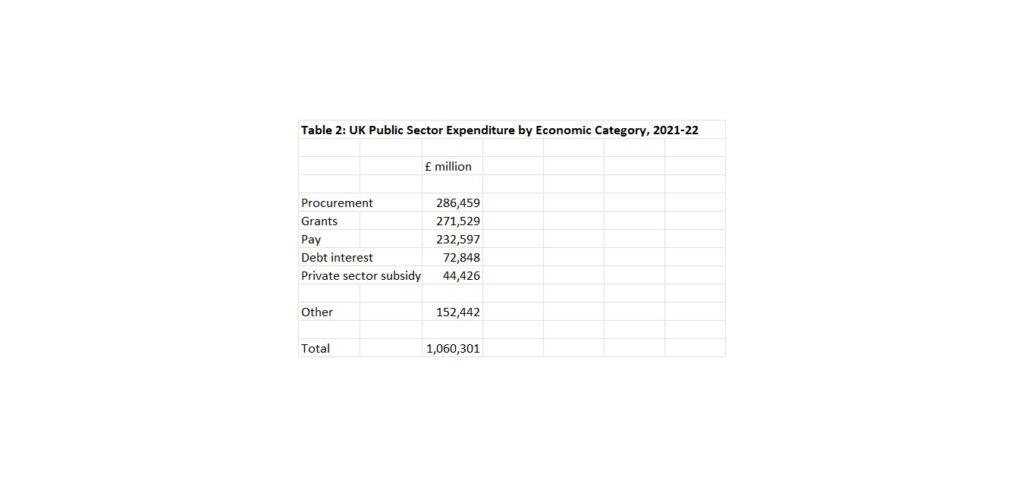

Table 2 shows expenditure by economic category across all the different divisions of public sector expenditure, broken down into the five largest categories, which between them account for 86% of total government expenditure (the data source is the same as Table 1). Procurement is the largest item, followed by grants (a big slice of these being old age pensions again), then pay, with debt service and private sector subsidy trailing far behind.

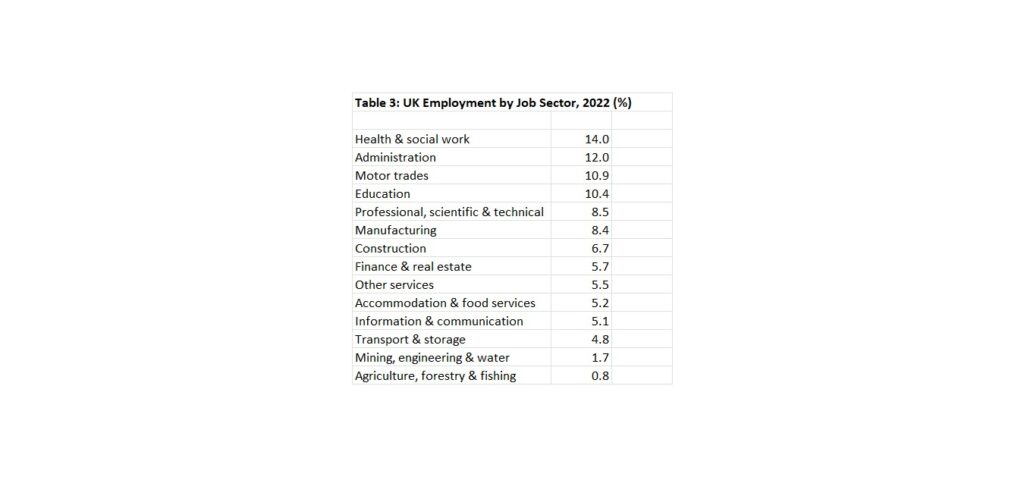

My final data presentation in Table 3 gives a breakdown of the UK workforce by employment sector (the data source is here). Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing is the smallest single sector, currently at less than 1% of the total workforce. In a small farm future, this figure would of course be a lot larger, demanding concomitant reductions from another sector or sectors. I’ll also note that the public service professions of health, social work and education between them account for about a quarter of the workforce.

I’m now going to suggest a thought experiment. Suppose the government announced that after some short period of grace – five years, say – all government expenditure and oversight of the economy would cease, save for military defence of external borders and due judicial process in relation to major crime. No more imports, government-backed financial instruments, or centrally-sanctioned banking. Probably also a ban on financial flows from abroad, and on people changing their main place of residence.

I admit that it’s a contrived, implausible and rather unpleasant set of suggestions. But I hope it might help focus attention on some underlying aspects of welfare.

(Editor’s note: I first drafted the preceding paragraphs a few days before the now ex-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng pronounced his disastrous ‘mini-budget’ on 23 September, the long-term consequences of which will probably align quite closely with the thought experiment detailed therein. So not such an implausible thought experiment after all! While the UK’s present woes were self-inflicted by an inept government, similar – or worse – circumstances seem destined to be the fate of many people worldwide in the longer term. All the more reason to really focus your attention, then…)

In the eventuality I’ve described, once people were fully disabused of the notion that the government was joking or that some other outside saviour would step in, I think a lot of them would instantly stop working in employments of a more abstract character that weren’t directed towards satisfying local material and social needs – which, by my reckoning, could amount to nearly half the jobs encompassed in Table 3. Many people would switch focus to producing food, fibre and other material requisites of everyday life. So there would be a lot of work in farming, forestry, construction, energy, water and manufacturing, albeit in radically changed forms from the present that emphasized low-energy input production for local need. Other people would dedicate themselves to maintaining and transmitting knowledge, and to supporting health and social connections locally, so there would also be a lot of work in education, health and community/social services. All of this would be no bad thing, in my opinion – we need to generate work in job-heavy, welfare-heavy, carbon-light sectors, into which the above could easily fit.

This work couldn’t be paid for in the way it now is, because in the new reality there is no money in the familiar sense. But even if there were, or if some new localized tokens of exchange were created, it would now be clear that money is only a means to the more important end of material and social community flourishing – food, clothes, shelter, health and human connection. So, looking at Table 2, we could at least in theory cross out most of that expenditure without really losing anything. People don’t fundamentally need pay or grants, and they certainly don’t need debt interest or subsidies. The givers and the recipients of welfare (doctors/patients, pension fund managers/pensioners, teachers/students, social workers/clients) in fact all need the same things. They need food, clothes, shelter, health and human connection. Much of this can probably be produced locally by people dedicated to its provision, making most of the expenditure in Table 2 moot. The main exception would be some proportion of procurement, on the assumption that there are things it would be good to have (X-ray machines, reference books) that have to come from somewhere and involve a cost of some sort that has to be paid somehow.

In other words, there’s a localist critique of commodity welfare provision which parallels the localist critique of commodity food provision. In both cases, our ability to provide for these things ourselves locally has been removed, repackaged and commodified as a specialist service and then sold back to us. Actually, that’s less true of welfare provision than food provision, since so much welfare is still provided locally by non-professionals. This applies, of course, to care for children from their parents, but also to adult-to-adult care, which is mostly received by elderly people. In 2016, 2 million UK adults received informal care, the majority from a closely related adult aged over 50. Meanwhile, participation in the existing world of formal work doesn’t necessarily allay welfare needs – a recent study found that the majority of people living in poverty in the UK were in a household where at least one member was in work.

So my opening gambit in relation to the question of providing welfare in small farm societies of the future is to say that these societies could possibly deliver many aspects of it as well or even better than our present heavily globalized and commoditized ones. A local society not geared to ‘employment’ but to furnishing local material and social wellbeing might unleash far greater human capacities to deliver welfare through unyoking people’s time, creative capacities and social engagement from the need to serve capital accumulation.

My position here is consonant with Hilary Cottam’s excellent book Radical Help (Virago, 2018), in which she argues for a shift from the dominant 20th century model of welfare, where relatively highly-paid professionals deliver services to people who are in need because something has gone wrong in their lives. As Cottam puts it, “The question is not how can we fix these services, but rather, as I stand beside you, how can I support you to create change … And the emphasis is not on managing need but creating capability …. At the heart of this new way of working is human connection” (p.15).

That sounds idealistic, and maybe it is – but Cottam gives numerous examples of local projects where the approach has borne fruit, based on a kind of mycelial model of multiplying local connections and relationships to which there’s no necessary end, as compared to paying people more or less handsomely in the present monetized economy to address unmet needs, to which there certainly is. She reports that William Beveridge, the architect of the postwar British welfare state, came to regret deeply that his model had failed to reckon with the importance of human relationships.

Given that my thought experiment by definition excludes government agency in manifesting these relationships, we have to ask what kind of local structures would deliver them. I’m going to leave that aside for the time being, because answering it is basically the same as answering what kind of politics it’s realistic to aspire to in a small farm future, and we’ll get to that in due course. But for a taster I’ll say that I’m increasingly drawn to the kind of answers apt to infuriate leftists and gladden the hearts of conservatives – individuals, households, families, schools, churches and voluntary associations (but some professionals too, no doubt). For now, I’ll simply add that if conservatives really took these things seriously, conservative politics would look very different from its present pallid state, while if the left took them seriously it would strike closer to the politics of human collectivity it theoretically espouses than present thin commitments to state provision. The key is to set people up for material and social livelihood by making the capability to furnish it widely available.

But that’s for another time. For now, I just want to posit the possibility that small farm societies of the future might potentially deliver a decent level of human wellbeing. I don’t, however, mean to overplay the rosiness of the future that awaits. So in my next post I’ll home in on a few specific areas of welfare and try to appraise some of the difficulties involved as honestly as I can.

I think about this a lot in my work for an agency that monitors and attempts to improve air quality. Up to 10 million people die prematurely each year due to air pollution, with 8 million of these due to burning fossil fuels.

Then looking globally at other issues – depression and anxiety rates are higher in more industrialized countries. Obesity rates are higher. Cancer rates are higher, although death rates from cancer are lower as a result of more advanced healthcare systems.

So long story short – we need more health and welfare provision in industrialized countries, and it’s pretty clear that it’s *because of* industrialization. Even many of the deaths and illnesses in less industrialized countries are the result of air pollution generated somewhere else and circling the globe. The Small Farm Future would avoid much of this.

In your thought experiment, after the end of government welfare, you suggest that “there would be a lot of work in farming, forestry, construction, energy, water and manufacturing, albeit in radically changed forms from the present that emphasized low-energy input production for local need”. It seems to me that this is true, but that there would also be a geographic mismatch between where the work would be and where people actually live.

Once a small farm future is established, it can provide for the welfare of its participants, but if the transition from urbanism to ruralism is fraught with misery, it will be a “valley of death” barrier to even starting a wholesale economic transition to localism. Every startup needs a large dose of initial support. Starting up small farm communities are no different.

The general population will need to be enticed into rural living. They will need housing, tools and equipment, training and that start-up support. It may be that large segments of today’s population can’t be enticed, especially the elderly, those in relatively a sound financial situation (who like where they are), those who are now primarily dependent on government support and those with very young children. It may be that young adults without children are the only people that would now be willing and able to take a chance on low-energy rural life.

But if we wait until the decline of our present economic model becomes obvious, it will be far easier for governments to ration essentials and keep people alive in their existing urban homes for just a little longer than send them to the country to get them off the government dole. Sending people to the country would be a far more expansive, and expensive, kind of support for the unemployed than dropping a few bags of grain and extra blankets on urban doorsteps. Moving people to new situations in the country could easily be beyond the capability of financially over-stressed governments.

I don’t think it will be that hard to convince young people that living and working as their distant ancestors did would be far more preferable than living in urban destitution, but even the young and fit will need a lot of help to make the transition (and they may need a taste of destitution for motivation). A fully functioning localized economy with multi-generational households might even entice the old and the young, but it’s the transition to “fully functioning” that’s the hard bit.

Waiting as long as we have, waiting until energy supplies are rapidly waning, has made any transition to a small farm future much more difficult. I sometimes wonder if it will ever be possible for people without the means to make the transition on their own to make the transition at all. I’m really curious about the politics and “local structures” you talk about that would make this transition possible. Please don’t hold us in suspense too much longer.

Diesel or the lack / cost of it will drive the political , food and financial future .

Siting in a block of flats waiting for a food truck running on cooking oil is a non starter .

Farmers complain now that they can’t get workers , when fuel gets tight and expensive they will need thousands of workers , hunger is a hell of a way to change society but it works , there will be trouble when the ration books come through the letter box , the offer of growing your own will be seen as positive , those that bought farm cottages will have to work on the land again commuting will be over , work on the land or live on starvation rations , your choice .

I read this morning that the German health minister is thinking of closing some hospitals , energy shortages are beginning to raise their head !

The experience with Local Welfare, the Poor Laws wasnt exactly a great success, and you will have the mis match between the more and less productive areas of the country and what they can or cant afford.

Some form of redistribution will still be at least desirable

Well said! I think Chesterton’s idea of proportion fits well here: some kinds of welfare are best done by families, some by associations and churches, and some by (local) government, etc.

I find the emphasis on mutual aid (which has a vibrant history on the anarchist/anti-statist left) or the “works of mercy” particularly hopeful because we can begin prefiguring it right now. The Catholic Worker Movement has been a great teacher to me in this!

Perhaps the greatest struggle is the cultural/moral shift to a society of people who take personal responsibility for the poor, rather than refer them to a welfare bureaucracy or call the cops on them for loitering.

Local systems are far more efficient than top down buracracy , this side of the pond churches and other groups do a lot more ” welfare ” than I saw in the UK , they also know the true needy versus the idle scroungers and ner do well / smack heads .

as for government ” welfare ” for those in the UK ,check out how much you are paying for national insurance versus keeping the money and buying a gold sovereign each time stoppages equal the price of a sovereign , in my accountant’ s estimation I would have retired with $4.5 million in savings at this summers gold price .

There will always be those that can not work but there will be fewer of them as the health services fail and many more who like me who rely on daily medication will be in dire trouble !

Bureaucracy is the disease not the cure .

I think if we become a largely rural, localised society then I agree that localised social care and welfare provision would likely follow. And it need not be a gap-filling approach because of abandonment by state agencies, which I think in reality underpinned the 2010 UK conservative Government’s Big Society philosophy. In fact I agree locally organised and delivered care might potentially do it better. However, when it comes to costly and high tech medical interventions that could be much more problematic. How would a low cost social-economic environment deliver, say proton beam therapy for cancer treatment – £250m for the two that are operate in the UK?

[You mean William Beveridge. Perhaps you conflated his name with Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary in Atlee’s Government.}

There used to be things called ” the cottage hospital “they worked very well , doctors and surgeons traveled around them ,Monday here Tuesday there , now you travel miles to a large hospital so the medics don’t have to leave their empire . Healthcare was certainly better when you lived in the same town and knew the nurses personally !

I recently bought a small farm with my wife and I work remotely part time. I commute once a fortnight now to the city V (2 hour by train where we live in Australia)

I read this article on the way in and it sort of primed me for the day. I work in tech and I honestly felt the biggest gulf with my life now on the land and those in suits around me.

I thinkI am in agreement with others comments and I think it will take a shock or two to really engage people in to exploring alternate ways than the current growth system but it’s steps like this in this community that perhaps can set the seeds for change

Thanks Philip for pointing out my Beveridge brain fade. I corrected it in the post to avoid propagating an error online (and not to conceal my mistake, perish the thought).

More controversially, perhaps, I also added a sentence to the post in light of John’s comment, to clarify that I am not opposed in principle to any form of (re)distribution and therefore perhaps not a fully paid up member of the conservative firmament in certain aspects of its anti-redistributive thinking. I just want to be clear about my club memberships. More on that in due course.

To Joe’s point, agreed that the devil is in the transition and that it’s likely governments will foot-drag about this and make the transition even worse – indeed, they already are. The valley of death may be spectacular, or much of it may manifest as it often presently does through avoidable mortality from heat, cold, damp, isolation and chronic malnutrition. The larger point of this present piece is simply to suggest that good welfare and small farm societies are not incompatible.

Joe, you’ve been reading this blog long enough to know that I have no magic answers to the politics of the transition! But I’ll try to further specify some aspects of it here soon. Think Goldilocks.

Thanks Larry and Philip for the comments on health. More on this next time. I’d say access to proton beam cancer therapy in a small farm future will be … limited. In that sense, it’ll be much the same as it is for people in the present world (maybe a bit worse, but not so much that it’ll make a difference to population health outcomes). At the same time, I think it’s worth emphasizing aspects of health status that would be improved in a small farm future, and the numerous aspects of health care that are job rich but capital light.

Thanks also Sean & Diogenes – let’s talk more about mutual aid, diesel & bureaucracy soon… And to Greg – I think you speak for many here in feeling growing alienation from the suits!

Hi Chris. It’s my first time to your blog.

If we are lucky, we will get a small farm future (how small is small?). We still have in our family ( 2 x 90yo parents + 4 x 50-60yo kids + 4 x 25-35yo grandkids) 3.5acre what’s left of an old farm, with cottage & barn made of cob, a well, plus a couple of other brick sheds. Obviously, that is a huge asset for our soon-to-be zero fossil-fuel (or renewable) future. The big questions are the relevant low-tech food-production skills and relevant tools. Our Dad grew all our fruit & veg when we were kids, but none of us or the grandkids knows how to do any of that, even with packet seeds and available chemical fertiliser etc (Dad used rotted pig manure from a farm up the road, and we had 3 large compost

heaps.

Low tech skills for the healthcare workers, clothes-makers, etc will be in very short supply – even today’s doctors, spoiled by x-rays & ultrasound, probably do not have their forebear’s skills in poking & prodding to diagnose what’s wrong, and certainly no surgeon knows how & what to do re low-tech tonsilectomies, etc.

Kind regards

Zoe

Skills are definitely a conundrum; that’s one reason that I’m trying to grow as many different types of my own household’s food as I can now, while we still have the option of buying something. It’s also part of why I grow vegetables in the churchyard for the soup kitchen, and teach anyone who wants to help out how to do a bit of it too. I’m a generalist so I also cook and preserve what I grow, and do a bit of spinning, a bit of crochet/knitting, reasonable amounts of mending which means lots of hand sewing, a good amount of foraging, and so on. I know how to weave and how to make a (very very simple) loom. This winter I want to learn to whittle, at least a bit. I said that last winter and didn’t do it, but this winter I will need a bunch of stakes for holding the sides of raised beds into the ground, so at the very least it would be good to make some of those.

But the skills deficit is not quite the problem that we are sometimes prone to believing it is in the industrialised West. An awful lot of fresh fruit and vegetables are sown, tended and harvested by hand. Machine knitting is a thing but machine crochet doesn’t exist, and every seam in every garment you own was sewn by a human being, either handsewing or sitting at a sewing machine, because we simply don’t have the technology yet for reliable handling of cloth by robots. (Some of the pattern piece cutting, I think, is now done by lasers, but that still requires someone to line up the cloth.)

I think with regards to the example of minor surgery there are a few big important things to bear in mind: one is keeping everything as clean as possible to avoid infection, one is anaesthesia, one is the expertise to make the tools. Control of bleeding is probably high up on the list too. But give your average surgeon today an operating theatre, lots of soap and water and alcohol, a decent metalworker to make the right tools, and someone who knows how much of which drug (there are a number of plant candidates for this, I don’t know how easy it is to get something like nitrous oxide without using huge amounts of energy but I can grow poppies myself) to administer to the patient without either killing them or having them wake up halfway through, and something like tonsillectomy or appendectomy or even a C-section isn’t going to be impossible, and is probably less risky than any surgery (in the West) in, say, 1600. The health risks and the practical costs will be much higher than they are (at least in the West) today, though, and something like brain surgery or organ replacement is probably off the cards for most people. (I hope it remains off the cards for me, honestly, because even today outcomes are pretty sketchy.)

I will confess to my envy of your 3.5 acres. If none of you currently know how to grow food, I would suggest that perhaps now would be a good time to start learning, while your parents are still around to give you some pointers. I wouldn’t bother with the currently available chemical fertilisers, though.

My father had his tonsils out on the kitchen table and even Sir Nigel Gresleys wife had a major cancer operation at home;

Military and ships doctors still have to improvise

Not saying that I would recommend it but it can be done.

You mention cloth production , today it is really cheap , and I mean cheap ! I have a loom it takes a couple of hours just to set up the warp setting up 600 threads and tensioning each one thru the heddle takes a lot of time and patience ! When I have filled the bobins and an ready to start I can do around 40 beats a minute , there are compressed air looms that can do 1500 beats a minute , I can make around a yard a day before my old bones start to complain . Cloth is CHEAP !

Might be of interest to the old-tech weavers.

https://faircompanies.com/videos/alpacas-turn-decaying-farm-into-thriving-slow-fashion-homestead/

Of relevance re modern health care going forward:

https://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2021/02/how-sustainable-is-high-tech-health-care.html

Yes. In a world without textile machines, textiles of all kinds are a household’s most valuable possessions. It’s easy to see why leather clothing was so common, too, in a low energy era. Prepping a hide is much easier than going through all the steps to weave an equivalent area of cloth.

But learning to do either weaving or hide curing is the last thing on my prepper list, since just about any modern closet has a lifetime supply of clothes and shoes in it. So, after skinning, my sheep skins go right into a compost pile. I’ll let any distant descendants worry about how they will clothe themselves. At least here in the tropics they can make tapa, which is a lot of work, but still a little easier than weaving, I think.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ndx0sJyUOzc

Lauhala (pandanus leaves) and coconut leaves can also be made into hats, mats, baskets and even clothing. I’m still using a mat I bought in Fiji 25 years ago. Very durable.

I can’t even imagine the work that goes into making a hand-knotted persian carpet. It makes spinning and weaving look lightning fast.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ECqbfX0IUA

We really enjoyed those films – never heard of tapa before. After getting a crochet kit last Christmas my daughter knocked up a (acrylic) hat in one weekend, but I agree that the rigmarole of actually producing weaveable fibre puts it firmly on the backburner for now. I did once sow a bed of flax but soon realised it would take more than the whole garden to grow a substantial amount of material, not to mention the knowledge, time and specialised tools. So yes, perhaps long before then leather chaps will make a comeback. Yee-haw to that!

(PS Joe I highly recommend the documentary ‘Russia 1985-1999: TraumaZone: What it felt like to live through the collapse of communism and democracy’. Utterly captivating.)

As a counterpoint, I made a nettle bracelet from scratch in a two-hour period in June. Specialised tools I used were gloves (nettles do sting) and secateurs (to cut the nettles at the base) and a kitchen knife (but a sharp rock would do) and a mallet. There’s no good reason the cordage I made couldn’t have been made into cloth instead of a bracelet.

I think most of the specialist tools for fibre processing are about increasing speed or improving quality (by removing dirt, bark, etc.). Making basic, serviceable twine or cloth is not that hard. Making cloth suitable for, say, a modern shirt that is worn with a business suit *is* hard, but I don’t see much need for it.

Flax is lovely, but I think in a survival situation I would go for nettle or hemp, or possibly perennial flax (I don’t know what the yield is like). The tiny nettle patch I harvested for the bracelet in June is ready for a second harvest now. I’m going to try making thread I can use to darn a hole in my favourite summer weight work trousers.

The thing that I see as a much bigger challenge is waterproofing. Here, animal fibres like wool that are still warm when they are wet are a real advantage. I’d love a sealskin hat to keep the rain off my specs but it isn’t happening anytime soon. I suppose I could try taking two layers of very finely woven cloth and putting a layer of latex (from dandelions, among other plants) in between, or making waxed cotton cloth using beeswax rather than paraffin, but wearing leather or shearling does sound easier.

Another challenge, but an easier one, is comfortable undergarments without the use of elastane. I strongly dislike hand knitting socks, and haven’t found commercial ones that are both fully compostable and also fit well enough not to be maddening. Other undergarments I have similarly crocheted or knitted for myself, to prove I can, but the time and effort that goes into so many small stitches is enormous and so for now I buy commercial, with a view to eventually making bras and underpants (or bloomers or whatever) from old t-shirts instead.

Regardless of all this getting into the (literal) weeds on textile manufacture, Joe is quite right that we already have a huge glut of serviceable fabric, some of which is very durable indeed. My own tinkering is more for interest and keeping a few small basic skills alive at a low level than a serious foray into self-provisioning or even efficient production.

I guess a natural/compostable waterproof fabric would be something like Barbour’s waxed cotton. The British military have experimented to similar ends in the past, including with nettles.

One of the flax fibre tools used looks like a large round comb, the tines or teeth all pointed metal much like nails, though it looks like a blacksmith would have produced this component. Various other handmade wooden objects for (I gather) gathering spun fibre etc were used too. You still find these artifacts in lofts and outhouses around here, along with sackcloth, often with initials stitched on… I must get the garlic in too!

I agree, there is a under valued pursuit of joy, meditation and achievement through craft that is essential as food. People will simply give up without it.

Simon, I’m pretty sure Barbour use non-compostable paraffin in their waxed cotton. In any case their stuff doesn’t fit me: the ladies’ wear is all far too small in the shoulders, and even if they did plus sizes they would be too short in the arms. The menswear is OK in the shoulders in larger sizes but then doesn’t do up because I have hips and breasts. I do have a waxed cotton cycling cape from Carradice that I found in a sale but I find it impractical for anything that isn’t cycling and the hood is too small. Making my own, and using some kind of biodegradable wax (maybe a blend of beeswax and vegetable oil?), is probably my best bet. Because the fit problems I have also apply to synthetic materials: a waterproof jacket that fits me properly is a very difficult thing to find.

Kathryn, a Bhutanese woolen hat design for you to divert the drips from your glasses:

https://hathorizons.wordpress.com/tag/textiles/

Thanks for this. I do actually have a hat with a brim, which does well enough for now.

We (Alice of the fibre and I) are working on a model of this from the ground up. We having a working plan for a farm with a care home at its centre, ‘unretirement’ homes, family housing and ‘warehouse’ communal accommodation for young people. We’re using a 200 acre farm as the scale and working on the assumption it has to be food, fuel and fibre self sustaining. At the moment it is quite surprising how much time is needed for care! But provisioning the rest leaves plenty of land for woodland and meadow. I would love to run the numbers by you to see if we are anywhere near realistic.

as a side note https://www.shtfplan.com/headline-news/dutch-government-to-seize-600-farms-at-gunpoint-claiming-nitrogen-is-a-pollutant

Looks like the government does not really care about your health and is willing to shoot you to stop farming

An awful lot of current medical care is pharmaceuticals. Many of these could be substituted with various herbs (though I am not suggesting a like-for-like substitution, and I think medical herbalism ultimately is pretty specialist and requires enough spare calories for people to be able to train in it full time), so perhaps “pharma” needs to be added to the “food, fibre and fuel” aims?

(N.B. I am already doing this in a very small way — growing plants that are therapeutic for me when taken as tea — and it is about as difficult as growing my own food, which is to say, I enjoy it, sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, and just as I’m glad to be able to buy pasta and rice when we have a terrible potato year, I’m grateful to be able to go to the chemist or even the GP if I get myself into real trouble on the medical front. I have treated minor-but-recurrent bacterial infections with garlic before now and it was pretty unpleasant for me and for the people around me, but they did at least stop being recurrent after that.)

While some vaccinations can certainly be done in a fairly low-tech way (e.g. smallpox variolation), in an ideal transition I would want to prioritise vaccination as something that’s moderately high-tech but very effective in terms of better health outcomes. I’ve never had smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus, polio, diptheria, or pertussis, and I’m glad of it. Lack of fast travel for the majority of people will reduce the speed with which novel pathogens can spread, and understanding of germ theory and indeed the principle of airborne (in addition to waterborne or fomite-spread) infection don’t need to go away just because we can’t keep making everything out of single-use plastic, but I’m still very grateful for that particular aspect of preventive medicine.

As Cottam puts it, “The question is not how can we fix these services, but rather, as I stand beside you, how can I support you to create change … And the emphasis is not on managing need but creating capability …. At the heart of this new way of working is human connection” (p.15).

Well, that rubbed me up the wrong way. I haven’t read Cottam, so may be responding to something other than her main argument, but I am very wary of some of these approaches. Too often I’ve seen “creating capability” used as a shorthand for “creating compliance with crapitalist structures” — all the rhetoric around getting people “off benefits and into paid work” is another example of this, ignoring that vast numbers of people receiving non-pension benefits are, in fact, already in paid work, and their lot could be improved drastically by paying them more instead of paying shareholders.

There will always be adults who are temporarily or permanently profoundly dependent on others for their day-to-day needs (feeding, dressing, toileting), and trying to force them into unsuitable work at cost of their quality of life and under the banner of “dignity”, is horrifying. And trying to support, say, someone who is homeless and apparently physically fit but has complex mental health needs into a pathway where they are compelled to endure significant distress in order to get back into a system which clearly wasn’t sustainable for them in the first place isn’t much better. I am not saying that you support either of these evils, or that Cottam does, but they are very close to the surface for me for a number of reasons (the guy sleeping in the churchyard who keeps putting his blankets on the leek bed, and won’t go to a shelter because people do drugs there; the spouse of a friend nearing the end of his life who has always been a bit anxious but whose anxiety is now in overdrive as dementia removed most of his prior coping mechanisms; my grandmother, who spent the last 15 years of her life needing help with feeding, dressing and toileting because of Parkinson’s disease, probably caused by the 1918 ‘flu pandemic; chronically ill friends being forced into “work-related activity” that is detrimental to their health… the list goes on.) Some people are easier to support than others but all of them are worth the effort. I think a needs-centred approach (like Finland’s “housing first” policy) is less likely to be abusive than a development-centred approach. The discourse around who pays (for housing, for dementia-appropriate companionship, for the care work of feeding/dressing/toileting) is fraught. Human connection is incredibly important, but it does not make these needs go away.

Like Sean, I am encouraged by the mutual aid, leftist-anarchist approaches to meeting people’s needs, partly because we can start to do this now — we don’t have to wait for collapse. (One could argue that for the guy sleeping in the churchyard, collapse is already here.) But I also worry about letting the disaster crapitalist class set the agenda, finding myself and my community in a constant state of patching up holes and papering over cracks in a system that is inherently exploitative (and which drives a severing of human connections) just to stop people starving. I am not an accelerationist — I don’t believe we should stop feeding people in order to bring about some magical revolution — but I do feel very strongly that any work that we do to “develop capability” should be work to develop autonomy from exploitative political systems, rather than work to develop competitiveness within the crappy terms imposed by those systems.

As usual I don’t have any easy answers to this conundrum or what it looks like, so I’m off to plant garlic. We’ll see whether my homemade compost is free of the allium white rot that is on the rest of the plot. Thankfully the churchyard doesn’t appear to have white rot, and the allium leaf miner hasn’t found the garlic there in the last two years, either. The squirrel, though, is a menace.

Unfortunately, I think the agenda is set by the people with the most power to set the agenda, who are now people with a vested interest in the global market economy (or at least capitalism at the largest scale possible). We can hope that if small groups of people get together to manage their own affairs, those groups will be left alone to manage as best they can, but I doubt that will be the case.

Managing life’s needs requires resources whatever the scale and current legal systems in most areas assign ownership to just about everything needed. It’s just not possible to go out and gather what is needed from one’s natural surroundings. Gathering or gardening/farming may be possible in the cracks of the current system, but self-provisioning at scale takes land and all the land is already owned by someone.

This situation produces the irony that people need to be rich to live as poor, self-sufficient farmers. The best things that could happen are either a new Homestead Act to allocate government land to new farmers or land redistribution from large landowners to new smallholders, both of which are anathema to the politically powerful.

I suspect that the curent powers-that-be will need to lose control before a small farm future is possible. That loss of control will come from economic collapse. I don’t see anything else causing it.

If the economy tanks a government strapped for cash with a little luck will stop farm subsidies , that will sort out the farmers from the corporate welfare leaches , there could be a lot of cheap land for sale when their subsidised investments bleed them out ..

Gathering or gardening/farming may be possible in the cracks of the current system, but self-provisioning at scale takes land and all the land is already owned by someone.

How enforceable is that ownership in a supersedure situation?

Land ownership won’t be enforceable, but a supersedure mini-state won’t be easy to organize amidst the chaos of collapse. It may be that nothing is enforceable and if collapse produces universal lawlessness (at least with respect to national law), it will be very freeing in some ways and very, very dangerous in others because that’s when the guns are likely to come out.

Land and weapons are two of the most basic intrinsically valuable resources people can own, land because that’s where everything humans need for life comes from and weapons because they can determine who controls the land. Throughout all of human history, land and weaponry have always managed to find each other and become intertwined. Collapse will make that entanglement even stronger, I’m afraid.

It is likely that the first thing a supersedure state will organize will be a castle, or something like it, and a militia. If de facto control reverts from nations to localities, so does control of the de facto armies.

I think a lot of this depends on the form and speed of collapse. But collapse is uneven, the planet has a whole range of diverse conditions, and there’s no reason to believe collapse must be the same everywhere.

Maybe it helps that I live somewhere that doesn’t have that many people who own guns. I am sure that guns are a convenient way of exerting power over others, but I think there are probably better and less morally destructive ways to reclaim land. I guess when the only tool you have is a bullet, though, everybody looks like a target. (And then when you run out of ammunition you’d better hope you haven’t shot everyone who can produce your food… not you personally, Joe, but the people who think that the most important thing to do is to stockpile ammunition!)

I know violence is a strong likelihood in the face of any resource constraint, obviously. We all know roughly how that plays out. Without discounting that reality, I’d prefer to explore more creative and interesting responses.

What happens if the cracks in our current situation get wide enough that the space between them becomes irrelevant? How can we work toward that?

I agree Kathryn. Those of us who are prepper-doomers can only work to make our communities and our families more resilient and hope that the worst forms of violence, like warlordism and widespread brigandage don’t happen to us. But we should also be aware of the potential for violence if only to increase our ability to avoid it.

By the way, I have a beehive that’s in a literal supersedure situation now. No queen to be found despite having a queen and three queen cells a month ago. No new brood means that the hive may very well perish. Let’s hope there is some slack in Chris’s analogy of the supersedure state.

Interesting intro. I’d like to see where this is going before getting too far into details, but I have some general comments.

First, I think it’s worth bearing in mind that the idea of Health and Welfare ‘provision’ emerges in our capitalist society, in which the key role to which we should all aspire is the productive worker. As mentioned in the post and comments, in the real world Health and Welfare are provided to people in work as well as out of work, but the guiding social assumption still tends to be that they are ‘safety nets’ to catch those who can’t work, at least at full capacity, and that things are ‘best’ when you don’t have to draw on either.

So there’s a distinction between the ‘productive’ and the ‘unproductive’ that’s truly insidious, and might alternatively be framed as one between the self-dependent and the other-dependent, in which self-dependence is lionised and other-dependence is a source of shame. To my mind, any ‘better’ future society needs to subvert this fundamentally.

Cottam’s book sounds interesting, and perhaps such subversion is what she’s getting at with a focus on human connection. The phrase used in Chris’s post, that a small farm society should deliver ‘human wellbeing’, is again a hopeful one if that wellbeing is delivered by all to all in various ways, and not simply from those with livelihoods to those without them.

But there may be a tendency, when considering a future of small farms, to promote self-reliance over other-reliance. Certainly if the ‘other’ is the capitalist state that is understandable and essential. But I think it’s worth considering that we need to create a society in which everyone is a bit more other-reliant – there’s no reason why those others need not be far more locally concentrated – but I would say we need to get rid of the aspiration towards a self-reliant ‘hero’ class. As Kathryn points out, the discourse around who owes what to whom always gets awfully fraught, but would be diluted considerably if everyone was giving something to everyone else.

I think interdependence and mutualism are good things. I also think most people in the industrialised West are far, far more reliant on the human labour of others than they think they are. There are still plenty of things that need to be done by humans using fairly simple tools (cleaning toilets in public buildings, picking salad leaves, sewing clothes) which largely rely on low-wage labour. One of the reasons I grow my own salad leaves instead is that I then don’t contribute money to a system where the owners of capital pay workers ridiculously low wages for their work and harm soil, wildlife etc while they are at it; it is not, for me, about self-reliance per se, but about increasing my autonomy from exploitative systems, partly so that when those systems collapse there will be alternatives, and partly because the exploitation itself is not something I want to enable.

All fair enough. I think it’s important to distinguish clearly between the two senses of reliance or dependence here – first, as you say, on a dependence on the global market place and its dodgy value chains, which we need to escape; second, what you style ‘interdependence and mutualism’. You’re clearly using them in different senses, but words like ‘self-reliance’ and ‘autonomy’ can bleed from one context to the other because of the way the worker in capitalist society is characterised ideologically as a ‘free’ agent in possession of their own labour power. I think that framing is built into the way Health and Welfare provision are currently understood in our society.

Hi Andrew,

This does feel like a really interesting point. And a possible counterpoint to the Distributist theory; is the kinship group scale able to support the wider community with their various contributions? How is this mediated with widely distributed dignity and validation?

My partner and I (Joel) are interested in ‘intersufficiency’. Larger tracts of land in trust with small (1 acre) plots of kinship or ‘housemates’, but also large tight commons and surplus systems that are specifically setup to support care of elders, children and contributors beyond physical Labour.

Our idea is that in the labour saving of operating on 200 acre scale, but with many more hands (60 at working stage; 2-3 days a week) you are able to create a resource skim that feels abundant, and eases the pressure of ‘clocking in without treading heavily on the land. All up for experimentation!

We certainly believe in a middle ground between the global commodity dependency of capitalism, and systems of isolated self-sufficiency, where wider care risks being externalised.

Maybe it’s a midsized farm future??! 🙂

Thanks Alice, this sounds fascinating! I’ve replied to some of this below Chris’s post, below, but it would be very useful to hear more about your project.

Sounds a bit like a village to me. I like it..

Thanks for some very interesting comments here and apologies for my inability to find the time to give them all their due in responding – not least due to family caring responsibilities, appropriately enough…

So – some interesting lines of discussion I’m not going to get into here, notwithstanding their importance: textiles, land/skills issues (but thanks for joining us here Zoe!), land/guns issues (we discussed that quite recently), land/politics/supersedure state issues (I’ll be discussing that soon), health care issues (ditto).

I will respond briefly to Kathryn’s comment and some of the subsequent points from Andrew & Alice (+Joel).

First, the capabilities approach isn’t what you’re suggesting, Kathryn. A key thinker behind it is Amartya Sen who, while he can’t help being a bit of an economist sometimes, has consistently emphasized in his work how to augment human wellbeing, not how to increase capital accumulation. One of the advantages of the capabilities approach is that it connects the ideas of needs and development, which IMO are more problematic standing on their own as welfare goals. I think Cottam’s approach is pretty good on this.

I agree with Kathryn that the question of who pays is fraught. The question of what they’re paying with is also important. Regrettably, I think the disaster capitalist class simply will set the agenda and any attempt to seize the controls of the state from it in service of more humane ends at this late stage in the game will be coopted by that agenda. So as I see it the broad answers to those questions are families and local communities will pay, largely with their time (which has always been the case, but will be more so in all likely future scenarios).

In facing this reality, I find myself possibly at odds with Andrew. I’ve got no inherent problem with the idea of other dependence – without other dependence, all of us would be dead within a few hours of birth, and so it goes on throughout life. Kathryn’s point about non-exploitive other dependence is important, and to my mind this is one major reason to emphasize localism as a probably necessary but not sufficient condition to avoid it.

But where I’m less in sympathy with Andrew’s take is the suspicion towards livelihood production and the notion of a self-reliant ‘hero’ class. As I see it, the productive worker isn’t a capitalist narrative but something very much more universal – rather, the nub of capitalism is to emphasize the endlessness of the work of capital accumulation while simultaneously undermining the ability of many people to contribute even to their own immediate self-reproduction at all.

This has become a really polarized and fruitless political debate, with too much victim-blaming on the right, and too much airy invocation of state/community responsibility on the left. Historically, many wise societies have seen the provision of food and other kinds of welfare as a collective responsibility, but with a lot of the day-to-day onus for realizing it vested in willing individuals who aren’t ‘heroes’ precisely because they’ve been set up to succeed at it mundanely by the wider institutions of their societies. As I see it, that’s going to be a key challenge for the small farm societies of the future, alas with little help and probably quite a bit of hindrance from existing state institutions.

Alice and Joel’s experiments are very interesting to me in this regard. How to harness different people’s contributions and needs across the life course and hand on responsibilities down the generations as present systems disintegrate is a key challenge. I’m all for experimentation, and I’d certainly like to know more. However, with care work as with food production I think there are some aspects that absolutely lend themselves to making commons of them and other aspects where this isn’t the case – it’s hard to get these boundaries right, and the work of doing so is continuous. So there are many challenges.

Thanks Chris. I admit I’m not quite clear where you think we might be at odds, but I’m sure it’ll come out in discussion.

The idea of paying for welfare might be a useful place to start. Payment, even if measured only in time, implies that welfare is something to be understood as an exchange – that wellbeing is only generated through the giving up of something else. Now, I realise that many caring roles are emotionally intense, that many carers give of themselves in order to fulfil these roles. But isn’t that just the definition of creation, or production?

Put another way, if we frame this around the subject of the previous post, caring should probably be considered a virtue, one of the most important – an end to which society should be organised. Framing it as something that is paid for by subtracting from the productivity of other sectors of life is, I think, problematic.

None of which is to minimise the scale of the infrastructure required to produce effective caring. Here I’m really interested in Alice’s point about the scale of the household within such infrastructure. In capitalist society, in which welfare is very much seen as a subtraction and is provided grudgingly, many find themselves caring for friends or relatives at the household scale because they can’t access help more broadly. The idea that welfare be produced at more intermediate scales is, I think, far more plausible, as it will offer far more opportunities for the forging of human connections that constitute the essence of wellbeing. There would be less scope for the polarisation of carer and cared for, which will always be a risk among the limited numbers within a household.

Finally, while I have some sympathy with the notion that those on left and right can be equally zealous at times when they would better spend their time building bridges, I’m wary of the idea that a polarised debate is necessarily always a bad one. In this case I think victim-blaming is precisely the wrong approach (not anticipating much disagreement there!), but that appeal to community agency is precisely the right one. Airy invocations can be frustrating (and I’m pretty sure I’m guilty of this), but can perhaps be thought about in the same way as your reluctance to offer a ‘blueprint’ for a small farm future – these structures are best developed ‘on the ground’ within the specificities of particular situations.

I am glad to hear that Cottam’s capability-based approach is better than I had feared; alas, I do agree that the disaster capitalist class will co-opt and attempt to disempower any threat to its own existence.

I think where the self-reliance/autonomy/productivity questions come in, it may be important to differentiate between production of goods and services to meet needs, and financialised ownership to profit from rents. Which is not to say that rents are always exploitative or that production of goods and services is always good; but rather that we operate under the constraints of whatever political structures exert power over us, and also under the constraints of simple biology (or physics of whatever): we must eat to live, and in order to eat, someone must labour.

Thanks for the new comments – just to pick up mainly on Andrew’s points, it wasn’t me who framed the issue in terms of ‘paying’ for welfare. In fact the drift of my OP was towards caring as a decommodified end in itself, so we’re probably in agreement there. Nevertheless, there’s an opportunity cost to caring that’s paid in other activities forgone.

I’m comfortable with the idea that the community bears this cost, just as I’m comfortable with the idea that the community bears the cost of producing enough food for its members to eat. But this is where the airiness of the idea of ‘the community’ kicks in. Who *exactly* within the community undertakes the care work, and who doesn’t, why do they do it, and how do the pros and cons of these arrangements weigh for the carer, the cared for and other interested parties such as the friends and relatives of the cared and cared for?

The issue exactly parallels the question of food production, which in low energy agrarian localist societies is mostly undertaken by people in the household that consumes the food, even when the site of production is held in common, such that ‘community agency’ consists mostly in enabling people to fulfil a self-provisioning function. In the case of caring for others, it may be that the net can be cast a bit wider in the community. I’m not sure. Even today in the UK, most care is provided by close family and I suspect this is as much despite our capitalist economy as because of it. The main problem in a capitalist society is that the tension and the opportunity cost of unpaid care work as a virtue versus paid wage work as a livelihood necessity presents itself very starkly.

In any case, I’d be interested to hear people’s arguments for and against caring as commons. There are certainly several I can think of on both sides.

The wider point of disagreement may be that I don’t think an aspiration to some level of self-reliance or to productive work is intrinsically bad or falsely heroic, and I don’t think community agency is intrinsically preferable. But maybe we’d agree that there are important roles for both. The devil is in the fine details of how such arrangements can work among all the idiosyncrasies of individual people and individual communities.

On that point, I agree with Kathryn about the difference between seeking to meet needs and seeking to extract rent. One of the major ways societies have tried to secure the former against the latter historically is by making households and families the key locus of food and care. Of course, that’s far from foolproof – but so are other arrangements. It’s interesting that family structures often ramify when other options for delivering care are limited. Anyway, thanks Andrew as ever for pushing thoughtfully at these points.

Finally, here’s hoping that Joe’s beehive experiences supersedure proper, and not mere emergency queen replacement or rank queenlessness!

I think casting the net a little wider than individual households and families might be beneficial in the case of people who require specialist education or specialist care. A Deaf child born to hearing parents, for example, or indeed a hearing child born to d/Deaf parents, will benefit from different opportunities for learning verbal communication than might exist in their family of origin. A blind person will benefit from learning Braille, but also from the existence of people transcribing books and music into the Braille format. (The glories of technology are such that there is now, if I recall correctly, a sighted-person-readable Braille font that you can download, so you could type a text, change it to that font, print it out on card, and then use a tool to make the appropriate raised bumps — much more easily than could be done by transcribing each letter by hand. I don’t think it works with music Braille though; I ought to learn more about that notation system at some stage…) I need physiotherapy every once in a while because of a connective tissue disorder, though several years after specialist diagnosis I am getting better at heading off problems before they get bad enough to need that sort of attention.

I think intergenerational care sometimes breaks down very badly in situations of abuse or dysfunction, and as ever I am wary of too much reliance on family or household units, though obviously this is also a problem here and now and wouldn’t necessarily be worse in a small farm future. This is not an easy topic for me for a number of reasons. I also think people who do not have children (for whatever reason) will of course still have care needs (as well as still having much to contribute to community and family life), and a bit more communal flexibility may be important there too. In short — the Levitical injunction to care for the widow, the orphan, and the alien is something we should take most seriously, and my instinct would be to expand that to more groups than listed.

The main problem in a capitalist society is that the tension and the opportunity cost of unpaid care work as a virtue versus paid wage work as a livelihood necessity presents itself very starkly.

I suspect that one of the difficulties I have in this conversation is that having grown up in a frankly dysfunctional family environment with sometimes quite inadequate care, in a wider backdrop of capitalism exacerbating this (at least to some degree), I do struggle to imagine communities where the default is that everyone receives adequate care. The way capitalist structures tend to frame work in terms of financial value and disregard anything that isn’t paid intensifies this, of course. I can try to work toward something better by doing some care work (as myself, but alongside and within a wider community) with people whose needs are unmet by capitalist structures, and I can try to believe that better or at least different structures are possible, but there are definitely times when this feels more like eschatology than politics.

I wonder how many people are in a similar bind when thinking about food production. I can imagine the majority of my own food consumption being vastly different than the current financialised industrial monoculture system, and working well enough, and I can imagine repeating iterations of that until we have something like a small farm future. I don’t claim that it’s an easy transition to make or that we’ll definitely get it right, I don’t claim that my own household will survive the upheaval on the way there, and if we do we certainly won’t be eating the same things we are now or living in the same places or doing the same work, but I am convinced that the possibility exists.

Thanks Chris, that clarifies a lot.

‘The wider point of disagreement may be that I don’t think an aspiration to some level of self-reliance or to productive work is intrinsically bad or falsely heroic’.

Not intrinsically, but certainly as currently mediated through capitalist society, which sets the productive against the non-productive. I’m sure there’s worthwhile pride in achieving a certain level of productive self-reliance outside those bounds, especially as a form of social bonding within household-scale units managing small farms, but in our current society it seems to me that people are more in need of reminding that intense emotional work can be more widely shared.

The devil’s in the detail, sure, but I do think those details are better worked out within larger groups. We’ve had conversations about families before, and I realise that familial relationships will continue to be hugely influential ties in future societies, but in the case of producing care it seems to me very limiting to assume that they should form the primary vectors. I think there are good arguments for managing and organising food production at household scales that just don’t translate into arguments for care production.

I don’t know if this implies caring as ‘commons’ – commoning is an approach to managing a shared resource, so what’s the resource in this case? If it’s human connection, then it’s shared by definition, and I would think there’s much to be gained by broadening the basis of those connections beyond the few faces of everyday household relations.

Anyway, I’m interested to see where this goes when you get into the details in the next post.

I’m not an expert on all the historical forms of care that existed outside the family, but even though there were probably care programs in monastaries, armies, sailing ships and other collective activities outside the context of multi-generational farming families, I’m going to make a wild guess that the vast majority of child care, sick care and elder care has always been within families and mostly performed by mothers and daughters.

I know that sometimes there needed to be an option for care outside the immediate family, but I’ll bet that it was mostly relatives that took in an abused child or a neglected elder. And in a village of small farmers it probably wasn’t too hard to find those relatives when needed.

I’ve also read that one of the techniques used by the elderly to ensure their care as they aged was to keep title to the family farm in their name until they died. This means that there was a real fear that if they signed over the farm to the next generation they would lose the leverage they needed to avoid being cast aside. This clearly means that there were, and are, families that could have members that shirked their filial care responsibilities.

Even so, I don’t think that the care system in general is something that needs to be reinvented for a small farm future. If most care is going to be delivered without purchasing it with money, who has better motivation to provide care and knowledge of patient history to make that care as appropriate as possible than the family.

As a family doctor in the UK, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how I might provide medical services in the event of an enforced re-simplification and re-localisation of society (I’m avoiding the word “collapse”). Most of my work at present consists of sitting at a computer printing prescriptions to go to the pharmacy and referral letters to go to specialists; in other words, co-ordinating other people to do the work rather than doing it myself. If we lost electric power, or computers were all disabled by cyber-attacks or EMP (electromagnetic pulse), or the supply of products to the pharmacy was disrupted, I would be sitting here typing instructions into a brick and I wouldn’t be much use to anyone. So I came up with the following Plan B:

1. Collect lots of books about basic medicine – the sort practised in developing countries where doctors have few resources other than their own hands; and

2. Reinvent plant-based anaesthetics, of the sort used in ancient Roman and medieval times. You can find an account of my progress with the latter on my blog “Toxic Plants”.

Thanks for those insights Peter. I’ll take a look at your blog – https://toxicplantsblog.blogspot.com/.

A few further thoughts on the points raised by Andrew, Kathryn & Joe:

I think it’s useful to think of commons in the context of caring. A basic definition of a commons is a resource plus a community plus a set of usage protocols. In the case of care, the resource is people’s time, capacity, skill and commitment to care for others. The community is … what? Maybe the immediate household or family of the person needing care, or wider family, or friends, neighbours, church congregations or other local groups? Does it include strangers who live nearby, professional service organisations, or distant taxpayers? And then there’s the protocols – who has a duty of care to me, in what ways and to what extent? I could say that people have a duty of care to each other, or that my community has a duty of care to me, but that’s too general. Suppose I badly injure myself on the farm this afternoon (which is quite likely – I’m going to be cutting blackthorn with my chainsaw), who *specifically* is going to care for me and under what terms? And would that look different in a small farm future?

Kathryn writes “I do struggle to imagine communities where the default is that everyone receives adequate care”. I do too, and I think this is an important point. I doubt any collectivity (family, neighbourhood, congregation, government) can ever provide adequate care. One thing they can do to help is set up the parameters to make caring easier – principally by enabling people to self-care and to enjoy giving care to others.

It’s interesting that ‘kinship’ and ‘kindness’ have a shared etymology. As Kathryn rightly reminds us, kin aren’t necessarily kind. But neither are non-kin, as evidenced among other things by any number of institutional care scandals. The kindness or otherwise of kin is a particular pinch point because it’s typically to kin that we express our vulnerability and needs. In many ways, that’s effectively what kinship is. So if we were to somehow abolish established family relationships, questions of care and kindness would merely reassert themselves in other guises.

I think Andrew is probably right that the arguments for household-scale food production don’t apply to care production in quite the same way and it’s appropriate to cast the net wider in the latter case. But in many ways I think the same arguments do apply – whether we frame them economistically (free riding, externalities, costs and benefits) or ethically (care, kindness, long-term commitment, reaping what you sow).

Kathryn raises another good point about those with and without children. This has become another baleful debate in modern societies, with the childless (particularly women) often censured for being somehow odd or selfish, but equally those wrestling with the cares of parenthood censured for the selfishness of their ‘lifestyle choice’ and suchlike. This will soon become a massive care issue, as globally crashing fertility rates in recent decades create a historically unprecedented high ratio of elderly people likely to need care relative to younger ones able to give it. I’ll write more about that soon.

So … lots of difficult issues here. I agree with Andrew and Kathryn that the capitalist political economy doesn’t make them easy. But they’re intrinsically difficult for all societies.

Right, off to cut some blackthorn – thoughts and prayers, please

I hope you did all right with the blackthorn. I am hankering after a traditional blackthorn walking stick — straight, with a ball at the top end made from the root. But that’s more a spade job than anything a chainsaw would deal with.

A lot of the answers to these questions will come down to how much food one farmer can produce.

Looking back at data from the late 1800s – early 1900s, 1/3 of the population were farmers. Working through old yield data corn produced 4 million calories per acre (160 square rods). Wheat produced 1.5 million and beans yield 2.2 million cal / acre. On average those three crops produced 2.6 million cal / acre.

Fruit and vegetables are necessary too but they are harder to store and typically aren’t as calorie dense. There are 82 calories in a pound of tomatoes compared to 1600 in a pound of corn.

People need 0.7 to 0.9 million calories per year. One person can take care of about an acre of crops by hand. How yields from today’s depleted soils and chaotic weather will compare is unknown. The long range climate outlook says that our drought will continue for a third year.

How are farmers compensated / cared for to keep from burning or wearing out ?

Fruit and vegetables are necessary too but they are harder to store and typically aren’t as calorie dense. There are 82 calories in a pound of tomatoes compared to 1600 in a pound of corn.

I don’t think anyone anywhere is suggesting tomatoes should be a calorie crop, they’re mostly water.

A pound of dried apples is more like 1200 calories; the dried apples still have more moisture in them than the corn, though. Apples are definitely harder to store than corn; they can be dried without the use of fossil fuels, though, and “a pound of corn” isn’t exactly unprocessed either, I need to get my popcorn off the cobs at some stage pretty soon. I have no idea how many calories per acre of orchard you might get, but an orchard also doesn’t require re-seeding every year like a cornfield does. We neglected our apple trees badly this year and still got a decent harvest despite drought.

I’m not suggesting that apples can or should replace corn as a calorie crop, but I do think a diverse and resilient growing plan should include both.

How are farmers compensated / cared for to keep from burning or wearing out ?

This is a good question, but it’s one that also applies to anyone doing any other kind of hard work under any kind of pressure. I am a gardener rather than a farmer, but I think things that could be good for farming include:

– seasonal working patterns where winters can be spent resting more or at least doing a different type of work than in the spring, summer and autumn

– avoiding predatory financing situations

– maintaining enough diversity that catastrophic crop failure in one species won’t take the whole farm down

Easier said than done, of course.

One thing about apples they are not a time intensive crop feed , pick , store ( or turn into cider ) peas , beans , grains take far more time to cultivate , veggies are time intensive to especially storing ( canning , salting, pickling ) soft fruits will be eat them while they are in season ( though some can be steeped in alcohol to make tincture / syrup ) .

It’s the bulk foods that take time ,field crops , it’s nice to have a tomato , but it’s a lot nicer to have potatoes in February .

Herbs for medicines will be a specialist job so you don’t accidentally poison yourself .

Tales of the Green valley and monastery farm on YTube give some good information on how they managed around 1600 AD . As far as I can remember they said six acres of grain Per Person was needed each year ,( though from the pictures it was a lousy crop ! )

Good line of analysis from Greg there. The sooner people start thinking of farming as a frontline welfare service whose workers’ own welfare is paramount, the better off they’ll be.

Don’t think I’m going to wade into the issue of how many farmers per capita population we need and the political/family/welfare implications just now. I’ve covered it in the past, but I agree it’s a critical issue – hopefully I’ll come back to it again one of these days.

The blackthorn treated me relatively kindly. Just a couple of puncture wounds, self-treated with surgical spirit – ouch!

Glad you’ve emerged from the blackthorn thicket relatively unscathed, and with disinfectant available. It hurts less than an infection would…

[…] examining questions of health and wellbeing in a small farm future, which I introduced in my last post. There, I made some general remarks about capacities for community self-care. In my next one, […]